Iron metabolism in heart failure patients is dysregulated, but it remains unclear whether these changes are pathogenic and detrimental, or adaptive and protective for the heart. Recent studies suggest that autophagy is involved in iron metabolism, so in this study, we examined the relationship between iron metabolism, autophagy and heart failure.

Kinya Otsu, BHF Professor and Chair of Cardiology, School of Cardiovascular Medicine & Sciences

02 February 2021

Iron release in response to stress may contribute to heart failure

A new British Heart Foundation funded study has found that the release of stored iron in heart cells may contribute to heart failure and could lead to the development of new drugs for the disease.

Using a mouse model, researchers from the School of Cardiovascular Medicine & Sciences have found that the release of iron in response to stress may contribute to heart failure and blocking this process could therefore be a way of protecting the heart.

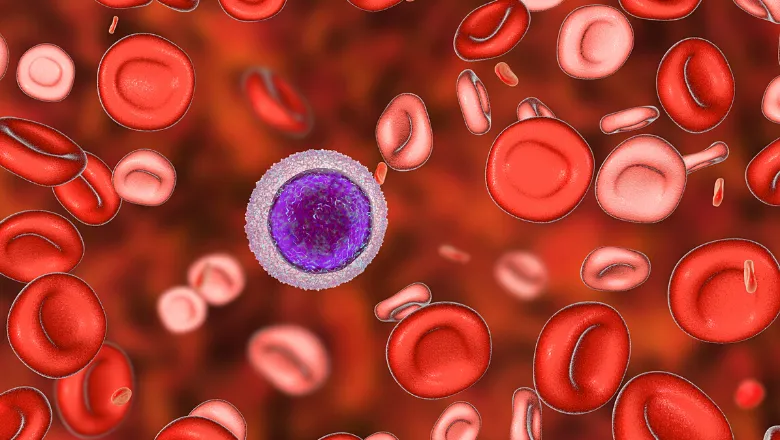

In the diseased heart, unwanted molecules can build up inside the cells. The cells then remove these unnecessary components and produce necessary molecules for the heart to function, such as amino acids and iron, in a process called autophagy. However, people with heart failure often have an iron deficiency, leading scientists to suspect that problems with iron processing in the body may play a role in this condition. The study, published today, explains one way that iron processing may contribute to heart failure.

The researchers studied a cohort of mice lacking a protein called the nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), which is necessary to release iron stored in cells when the body’s iron levels are low. It was found that the NCOA4-deficient mice did not develop excessive levels of iron or a build-up of unstable oxygen molecules that can lead to cell death in heart failure, compared to mice with the protein.

A compound called ferrostatin-1 is known to inhibit the release of stored iron and reduce the accumulation of unstable oxygen molecules. Additional investigations by the team showed that treating mice who have the NCOA4 protein with ferrostatin-1 can reduce the amount of cell death in cases of heart failure.

Further research is recommended to understand the step-by-step process of iron release and to test whether inhibiting this process could be beneficial in human subjects.

Patients with heart failure who are iron deficient are currently treated with iron supplements, which previous studies have shown reduces their symptoms. While our work does not contradict these studies, it does suggest that reducing iron-dependent cell death in the heart could be a potential new treatment strategy for patients.

Kinya Otsu, BHF Professor and Chair of Cardiology, School of Cardiovascular Medicine & Sciences

Read the paper published in eLife.