06 December 2021

Is the 'wall of money' heading towards climate change mitigation making a difference?

Iva Koci, PhD Student Accounting & Financial Management

The urgency of climate finance

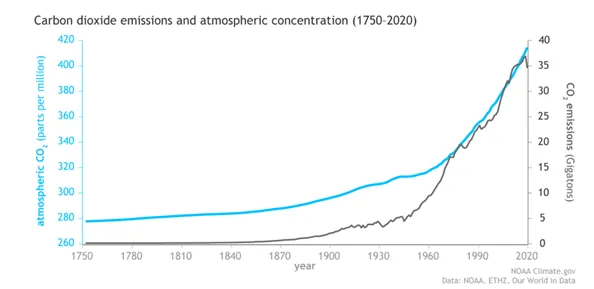

During most of human history, the concentration of carbon dioxide has been almost stable around 280 parts per million (ppm). But, since the dawn of the industrial revolution, we have intensified our use of fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas and oil.

This has generally led to a much more comfortable life for many but has consequences for future generations that are already being felt in the greater frequency of extreme weather events in some parts of the world. Earlier this month, in Glasgow, one of the powerhouses of the industrial revolution, world leaders gathered to tackle potentially the most critical crisis in humanity: climate change.

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a global coalition of leading financial institutions committed to accelerating the decarbonization of the economy, pledged $130 trillion (US) of capital to achieve net zero by 2050. That’s an ambitious total; think of the fact that the world’s GDP in 2020 stood at USD $85 trillion (US).

How much capital have investors committed to climate change?

Estimates of how much climate finance is flowing around the world depend on who is doing the counting. The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), an international thinktank that publishes an annual analysis, says that the total flow of climate-related funding was $510-530 billion (US) in 2017. The UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), put it at $681 billion (US) in 2016. But all these bodies readily agree that both the private and public markets have an important role to play to provide the future immense funding.

The investment community is therefore expected to play a significant role in driving real progress towards a net zero resilient future. This could be achieved via two main channels. The first is through capital allocation decisions: investors can choose to provide funding to innovative firms and climate start-ups and to divest from carbon-intensive firms. For those investors for whom divestment may at times not be an option, for example passive investors who track a broad index, the second channel of engagement becomes more relevant.

Investors should practice responsible oversight and stewardship of their capital, emphasizing direct dialogue with the investee companies and performing independent research and analysis to carefully arrive at the proxy vote decisions. Participating in the proxy votes of their major holdings is an important way for engaged investors to influence corporate behaviour on Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) issues. By voting to promote greater management accountability on issues from climate change to diversity, investors can help improve risk management, long-term return potential as well as incentivise positive change.

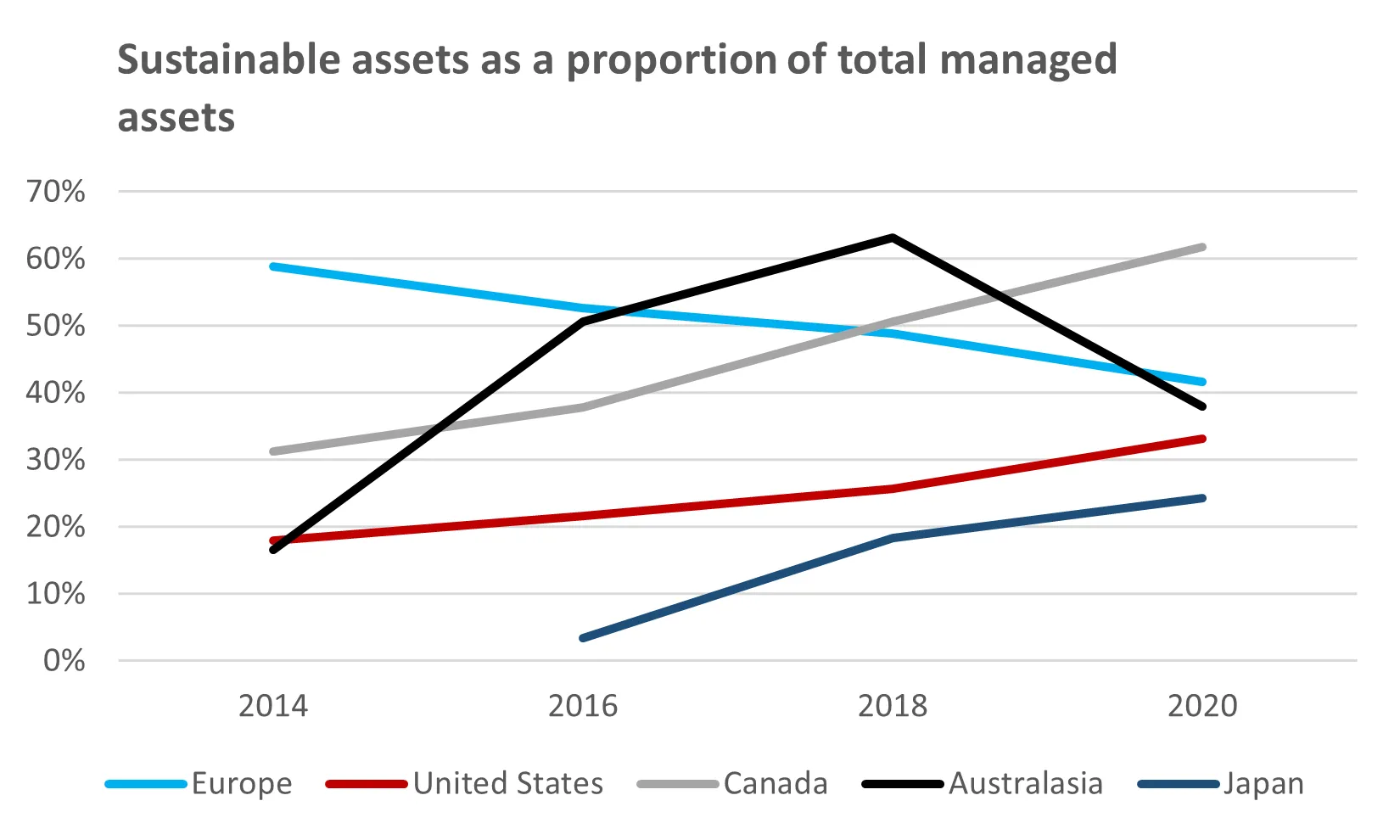

The proportion of sustainable assets relative to total managed assets has swiftly accelerated in the past decade as investors have formed coalitions in response to the systemic risk posed by the climate emergency. The largest coalitions such as the United Nations PRI (Principles for Responsible Investments) signatory institutions, Climate Action 100+, or the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance have made bold commitments to provide the capital and engagement for carbon transition.

Are investors’ climate change initiatives making a difference so far?

While research suggests that institutional ownership, i.e. the proportion of a company’s shares owned by institutional investors like pension funds, asset managers, or university endowments, plays an important part in driving positive ESG performance, my PhD dissertation on one high profile institutional investor-led initiative found little evidence of delivery on the promise to curb target companies’ greenhouse gasses.

I looked at the Climate Action 100 (CA100+) investor-led initiative, which is active across 33 markets. The CA100+ has made publicly available the list of 167 companies that it is targeting, which it says account for over 80 percent of corporate industrial greenhouse gas emissions. I compared these 167 companies with a matched controlled sample of other large emitters that are not on the CA100+ target list.

Despite the influence that you would expect the CA100+ to have through its $60 trillion (US) in assets under management, I found little evidence that CA100+ activities are having an impact on the companies they have targeted. Similarly, other researchers established that stocks held by UN PRI signatories were actually involved in increased number of incidents and events that may pose both business or reputation risk as measured by the ESG data provider Sustainalytics.

This leaves us questioning how smooth the hoped-for transition to net zero will be. Despite the vast sums investors have pledged to tackle climate change, will the costs be ultimately borne by future generations and countries that are vulnerable to climate change – in other words, by those who did not cause the problem in the first place?

Of course, there is a significance in pledging $130 trillion (US) at the COP26 and in gathering like-minded investors to prove direction and commitment; it sends a clear signal to the market. However, despite ever increasing regulation, more targets and better integrated sustainability reporting, we still need to maintain pressure on our pension fund managers, university endowments and the general investment community to really invest for our future.