04 November 2019

The "women's vote" is a myth: the average voter is a female voter

Rosie Campbell

ROSIE CAMPBELL: With women making up over half of the electorate, election strategists would be best advised not to ignore their potential for driving election results.

This piece was originally written for the Global Institute for Women's Leadership's new Essays on Equality publication, which features contributions on a range of different issues by leading researchers and figures working on gender equality.

Read the full collection of essays

A staple of every election is a discussion of the “women’s vote”, as if women are distinct from the “normal” votes cast. Given that women make up 51 per cent of the UK population and an even greater proportion of eligible voters – and are just as likely to vote as men – the average voter is in fact a woman.

The average voter behaves differently from male voters in some ways. Women are disproportionately represented among undecided voters, and they tend to make up their minds who to vote for closer to election day. In 2017, for example, data collected in April and May in the run-up to the British general election showed that 18 per cent of women compared with 10 per cent of men said they did not know who to vote for. Women say that they are less interested in politics than men (70 per cent of men and 62 per cent of women reported being interested in politics in 2017), although this gap is reversed when women are asked how interested they are in specific policy areas such as education or health. Women are also more likely to select the “Don’t know” option in political attitude questions and on average score slightly lower than men on political knowledge measures.

But in the end, women are just as likely to vote as men. Indeed, in raw terms, women are slightly more likely to vote than men, although this is due to women’s greater longevity combined with higher levels of electoral participation among the old; turnout among women and men of the same age is pretty similar. The growing “grey” vote is much more a female vote than the electorate overall.

There are also consistent sex differences in some political attitudes. Women tend to favour increased taxation and spending on public services more often than men, and they are less likely to support cuts in expenditure on key public services (health and education in particular), perhaps unsurprisingly as such spending cuts have a larger impact on women than men. Women have more egalitarian views than men on a number of issues: they tend to be more progressive on gender equality and less often express racial prejudice or homophobia than men. And there are differences in what political scientists call salience, the priority men and women attach to particular topics. Women report more concern about education and health, while historically men gave relations with the EU and taxation greater priority. But in recent years the gap in strength of feelings about the EU has declined, and there was not a significant difference in the way men and women voted in the 2016 EU referendum, even though men remain slightly more likely than women to be more fervently anti-EU.

All of the above is well-documented. But the truth about women voters is more inconvenient for those who would find it easier to trot out a simple narrative about what women want. The reality is that there is no single story to tell about women voters. They are not some homogenous group that party strategists can target with ease; they are as divided in their opinions as men are. Moreover, although there are differences between women and men in their political behaviour, the similarities are often much stronger. This was especially true when it came to voting – since 1974 female voters usually behaved in largely the same ways as male voters – or at least it was until 2017.

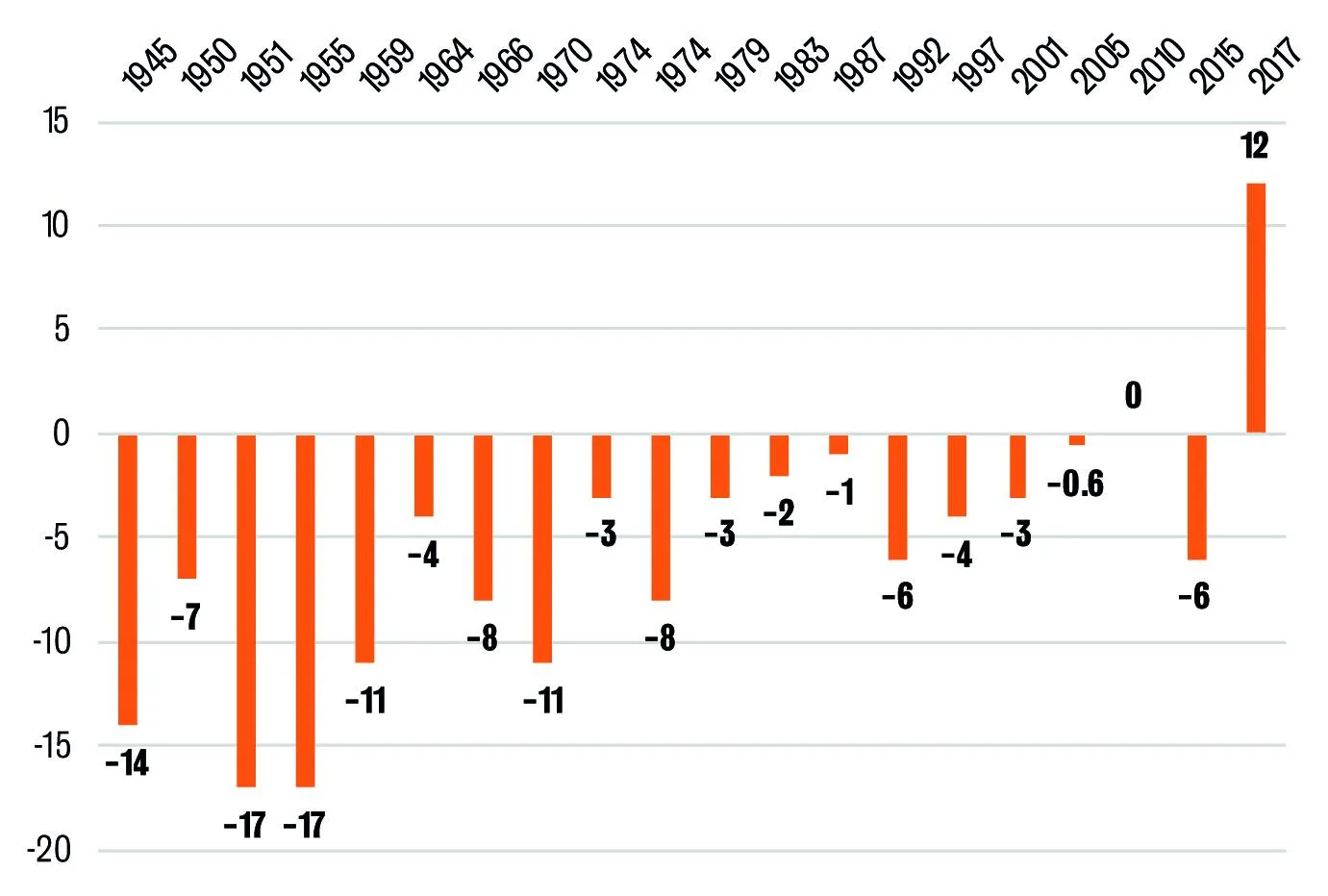

Historically, women voters tended to be slightly more likely to vote Conservative than male voters. New Labour managed to reduce this advantage by picking up the votes of younger women, particularly middle- and higher-income mothers, but in most recent elections the overall picture was one of little or no difference in support for the main parties between the sexes. The chart below illustrates the gender gap in support for the two main parties from 1945 to 2017; it is calculated as the difference between the Con-Lab lead for women and for men. A positive score indicates that men are more likely to vote Conservative, a negative score that women are more likely to do so. The decline in Conservative leanings among women voters is apparent, and from 1974 to 2015 the gap rarely reached statistical significance. Given the numbers involved, these differences may still affect the election outcome, but it also means that they were small enough that variations in the gender gap in individual surveys can be produced by random error.

In 2017 we saw the first election where significantly fewer women voted Conservative than men, with the Labour Party eight percentage points ahead among women compared with men. This produces a 12-point gender gap, larger than that seen in any election since the 1950s, and one that is in the opposite direction to the historic trend.

This reversal of the traditional party gender gap might represent a tipping point where the UK’s electoral politics begin to mirror those in the US, where more average voters than men have supported the Democratic presidential candidate in every election since 1980. However, before announcing that the American gender voting gap has come to the UK, we should exercise a little caution, both because 2017 was merely one election and because of the unique circumstances of that one election, in which a late swing played such a large part in the result, since that late-swing will have involved more women than men changing their minds.

So we cannot tell at this stage whether 2017 was a blip or the start of a more fundamental realignment in British politics, with the gender gap flipping directions. Either way, election strategists would be best advised not to ignore the potential for average voters to drive election results.

Rosie Campbell is a Professor of Politics and Director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King's College London.