In one of the first analyses of suicidal attempts in people displaying the characteristics of BDD in the general population, we found a quarter had attempted suicide.

Dr Georgina Krebs

10 February 2021

How the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) are tackling mental health challenges in children and young people.

Clinical psychologist Dr Georgina Krebs has dedicated her career to helping young people deal with agonising mental health issues like obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Through research, she’s improving treatments and finding new ways to help young people who might otherwise slip through the cracks, giving them the support they need to live happier, healthier lives.

‘While training to be a psychologist at King’s, I fell in love with the idea of helping young people with OCD. People think OCD is just washing your hands a lot, but it’s so much more than that. It’s an incredibly varied and disabling condition that tears lives apart, especially for young people.’

Treatment usually includes cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). For OCD patients this involves gradual exposure to situations that trigger obsessional fears, while also resisting the urge to carry out repetitive behaviours to reduce their distress. This retrains the brain to deal with anxiety and stress in a different way. Most patients respond well to CBT and improve but around a quarter don’t respond at all and many others only achieve a partial recovery.

One key group with high rates of OCD and generally poor treatment response is young people with autism spectrum disorders but, as Dr Krebs explains, a bespoke CBT approach brought some unexpected benefits:

‘We recently tested an adapted version of CBT for these patients, making the sessions very structured and incorporating a patient’s special interests wherever we could. The results suggest it will be more beneficial for these young people, reducing not only their OCD symptoms but also – and we didn’t anticipate this – reducing repetitive behaviours associated with their autism spectrum disorder.

Other studies support the idea that a holistic family view is vitally important, as Dr Krebs explains:

‘We found that it’s very common for parents to “accommodate” OCD through their own actions or words. This is completely understandable, as parents are trying to reduce their child’s distress, but it has the unintended consequence of enabling OCD behaviours and fuelling fears. That generally means treatment is much less likely to work, unless these parenting behaviours are directly tackled within the treatment.'

‘By understanding a child’s physical health, any other mental health issues, genetics, family dynamics, school, friendships - all the unique factors affecting their mental health - we can tweak and shape existing therapies so that they are much more likely to work.’

Seeing things differently

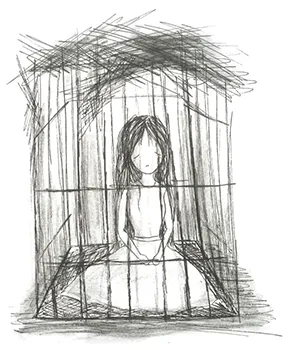

While things are moving in the right direction for OCD, Dr Krebs is concerned about progress for young people with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). The team’s research suggests around 79% of 11-16-year-olds are concerned about their appearance. Some of these young people will develop an extreme manifestation of appearance anxiety known as BDD. People with BDD cannot stop thinking about imaginary flaws in their appearance, to the extent that it becomes impairing and can completely take over their life.

‘BDD is vastly under-researched and poorly understood. In one of the first analyses of suicidal attempts in people displaying the characteristics of BDD in the general population, we found a quarter had attempted suicide. We found that 40 to 50 per cent of children aged 6-12 say they are not happy with their appearance. A quarter. To see such a high percentage in a non-clinical group – not only those who have sought professional help – was incredibly sobering.’

In 2015, the team carried out the world’s first trial of CBT for BDD in young people, finding that it has great potential to help but that more research is needed to improve and tailor the treatments.

‘I’m hopeful that we can improve things for young people with BDD, OCD and related disorders, because they are out there and they are struggling. I know that I’m in the right place to do this work – there’s nowhere else like it in the UK.’

Dr Krebs and her team are looking forward to 2023, when the new Pears Maudsley Centre will open its doors, bringing care, research and education together into one state-of-the-art space designed specifically for young people.

To find out more about the new centre visit: maudsleycharity.org/whats-on/pears/