Suddenly we were pressed to say something that would resonate beyond the academy, and especially because we feel so passionate about this work, we knew we wanted to do what we could and add to the conversation and try out ways to do this from the very beginning.

Dr Caitjan Gainty, historian and Senior Lecturer in the History of Science

24 March 2022

Poison, Burn, Cut: King's Artists project explores 'healthy scepticism' within cancer treatment

A collaboration between a filmmaker and a historian of medicine that aims to push healthcare to new bounds.

Written by Stephanie Reed, fourth-year dentistry student in the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences and student digital content coordinator, King’s Culture

Helmie Stil is an award-winning filmmaker and Dr Caitjan Gainty is a historian and Senior Lecturer in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine in the Department of History in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities. The ‘unlikely’ duo is pairing up alongside a team of creators and activists to form a short film to show what it is like to be treated for cancer as part of the King’s Artists Programme. This project is part of the Wellcome funded Healthy Scepticism initiative designed to push healthcare to new bounds.

One in two people in their lifetime will be diagnosed with cancer and the project seeks to represent how patients feel in the process of being treated for this disease: ‘poison’ of the chemical insult in chemotherapy, ‘burning’ using radiotherapy and the excision of cancerous tissue by a ‘cut’. These are treatments which one would think might have developed drastically in the rapidly advancing medical field. And yet, they have remained remarkably unchanged.

The focus of this contrasting yet complimentary pairing between Helmie and Caitjan is to work together to produce an animation to demonstrate an accurate and representative view of cancer in healthcare and give patients a platform to communicate to others within the healthcare ‘bubble’ and outside. Caitjan and Helmie work together to encapsulate the severity of cancer therapies, spotlighting particularly the changes or lack thereof in the nature of these treatments.

Within the broader Healthy Scepticism project, they are teaming up with communities whose needs have not been met by the current healthcare system, performing a unique investigation where these individuals produce their own research into these issues. The advantage of this is that the individuals are offered a platform to collect data themselves rather than being studied externally and experiencing the barrier between academia and the individual culture of their communities.

In a short interview with the creators Helmie and Caitjan, I received an insight into how they felt about the project.

As the pandemic erupted, there was a global healthcare crisis which, they said, brought the Healthy Scepticism project into function. The healthcare system was spotlighted more than ever before and this further drew on a requirement for this platform.

Before my research into the healthy scepticism project I was of the opinion that scepticism was the opposing view to the scientific viewpoint. Caitjan, however, highlighted that science has always been developed by disproving previous theories in order to develop more accurate and better ones and that ‘scepticism often gets a bad rap, as something that is destructive or problematic’. According to her, scepticism of healthcare is not the opposing argument, but rather the driving tool at the forefront of healthcare’s development. The enemy of development is not distrust in healthcare but the tunnel vision that it is simply a science rather than a multifaceted structure requiring complex social considerations.

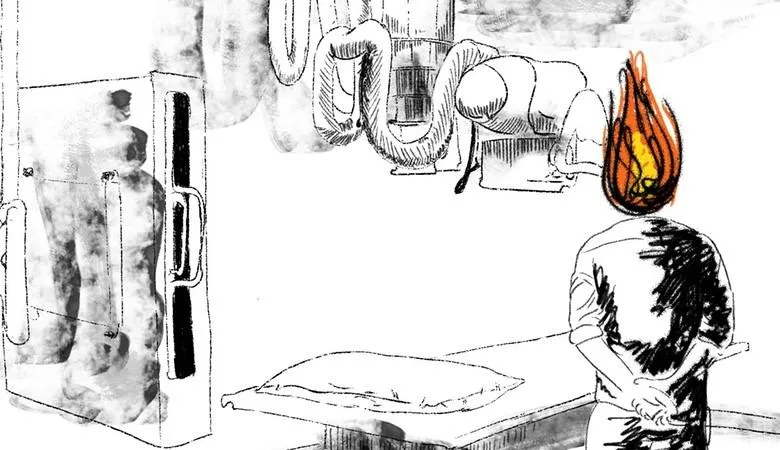

The artistic initiative is also very important as it provides a language more of us can understand. An animation evokes feelings and emotions in us and translates the experience in a unique method which cannot be encapsulated in the written word, holistically approaching our healthcare understanding and development. The creators worked with cancer survivor and activist Grazia de Michele and author of The Cancer Problem: Malignancy in Nineteenth-Century Britain Agnes Arnold-Foster, as well as with animator Dominic Davis, alongside getting inspiration from patients’ experiences. Helmie described the influx of scientific and historical information, which then inspired her to produce some sketches with a character with a missing piece (Cut), a character with his head alight (Burn) and a character aglow (Poison). It was also of significance to pay attention to the past and current treatments, leading to the provision of juxtaposing contemporary and historical footage alongside the animation to hone in on this aspect.

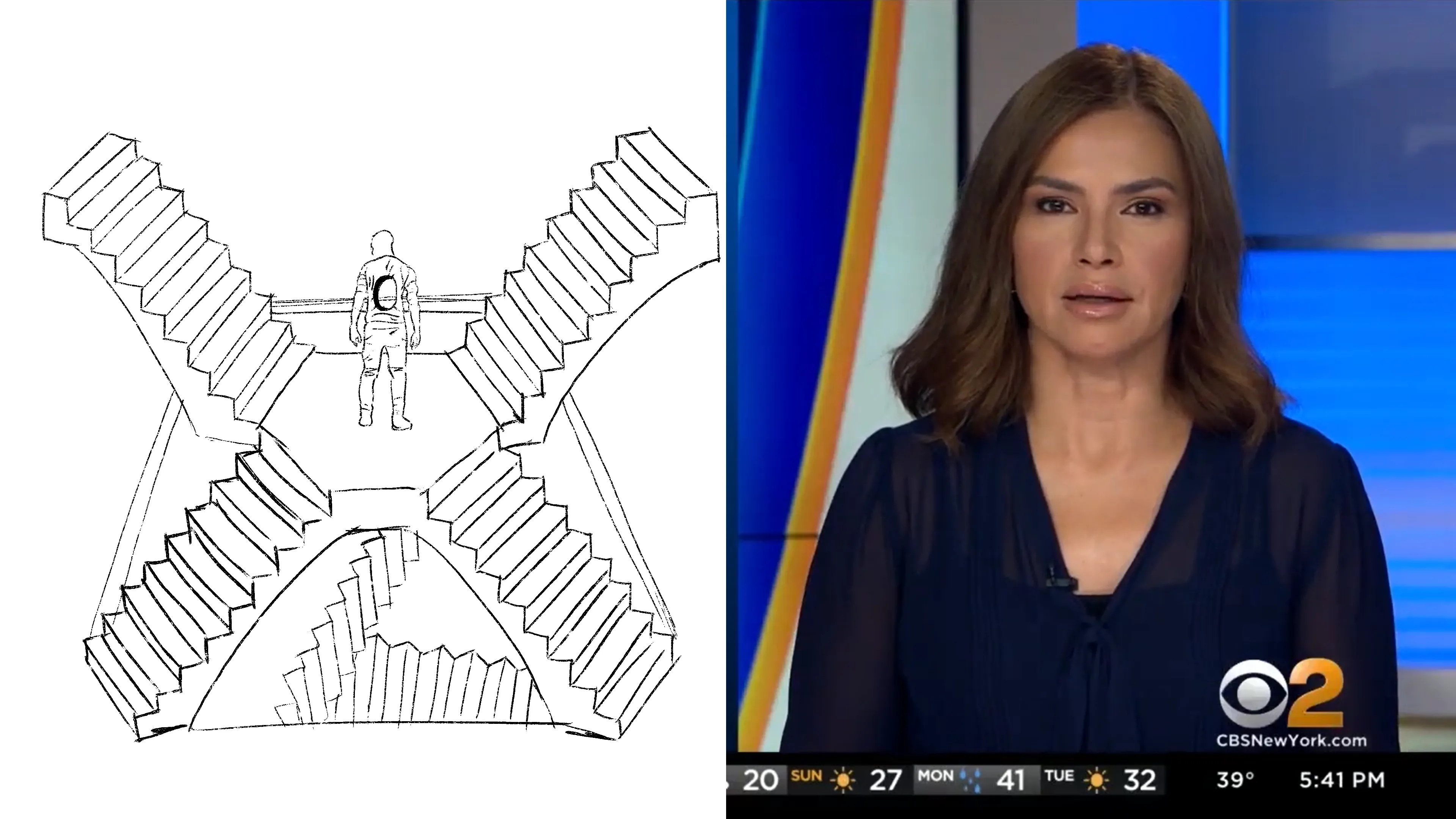

So, after lots of talking and thinking we went for the feeling of feeling lost. In the film we use a staircase, sort of an Escher kind of staircase, where the characters fall, climb up and walk in different directions to emphasise this feeling.

Helmie Stil, filmmaker

From stepping out of her artistic realm into this more academic and medical world Helmie saw how history is repeating itself, which was both a realisation but also an understanding of the importance of knowing the history. Caitjan spurred on Helmie’s artistry by encouraging her to think outside of the “main thoughts”.

This has also helped me appreciate how important the history of medicine is. The project shows how we can learn from the response to these treatments historically and rather than repeating history, develop a medical field in which we understand each other better. The historical aspect doesn’t seem as obvious, but there is a real focus on the importance of seeing what has been done before to learn from it.

In an era in which we can culture spinach to produce heart tissue, it is not uncommon for patients to be shocked that sometimes the only option to replace missing teeth is a plastic denture. As a dentistry student I understand how these treatments can seem disheartening, and it is difficult when this is the only option a patient is given. My overall take on this project is that I am grateful for the lateral thinking and dedication to drive development in healthcare to make it for everyone, and by everyone, increasing in that way faith both in healthcare and in people’s representation. I found it particularly interesting that despite the length of time dedicated to treating cancer, the treatment is not as advanced as one may think. This is not to undermine modern medicine but to think how we can think differently to get different results.

So we’d definitely like to see a change in that world view, where this binary gets broken down and we can see the world of health and its care as something that is productively much more diffuse than our rhetoric has tended to make it seem.

Dr Caitjan Gainty historian and Senior Lecturer in the History of Science

King’s Artists provides opportunities for artists to be resident within faculties across the university and aims to support residencies that place artists in collaboration with students and staff across disciplines to embrace creativity and take risks, developing new thinking and creative outputs.

King’s has a long history of hosting and working with artists across its faculties and within its wide range of research areas, bringing together nearly 60 artist residencies that have connected academic research with art through a range of media including painting, printing, literature, theatre, music, performance, installation, photography, video, textiles, waxwork modelling, ceramics and fashion. Many of the artists and academics have presented the work and research developed at King’s during residencies on national and international platforms.