01 December 2017

Organizational Changes in Higher Education: Mergers, Acquisitions and Novel Collaborations

Following on from their recently published report (Ferlie and Trenholm, 2017)

Following on from their recently published report (Ferlie and Trenholm, 2017), Ewan Ferlie and Susan Trenholm from King’s Business School here extract key issues that the UK Higher Education sector might well consider about the major organizational changes and pluralization now emerging.

UK Higher Education (HE) is shifting from its previous form as a planned and nationalised sector and is undergoing pluralization by becoming more: market driven, globalised, focused on students as paying customers and also (somewhat) more diverse. The recent extension of Degree Awarding Powers (DAPs) sought to stimulate new market entrants and disrupt incumbents and may well be doing so.

What are the implications for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)? Obviously, market pressures may stimulate Mergers and Acquisitions (M and A) activity as ‘squeezed’ HEIs merge with stronger institutions. There have been some mergers in the sector, and more may well follow. Our review found risks attached to such mergers, not only in loss of institutional independence but also threats to the acquired organization’s underlying culture and identity.

We also looked at M and A literature in related knowledge intensive sectors (e.g. bio pharma and professional services) suggesting many mergers did not improve the acquiring firm’s financial performance. Where there was good organizational fit between the two parties, outcomes were better. Where the partners bring complementaryknowledge assets (rather than similar or dissimilar ones), the prognosis was better, then, too. The literature suggested that the post-merger period as well as the decision to merge needed to be managed carefully. The mismatch between two different organizational cultures could be a powerful change blocker in mergers. The active presence of key leaders acting as knowledge brokers and lateral linkers across organizations was important. So we were cautious about a headlong and ill thought out rush into M and A across the HE sector.

As well as reviewing M and A literature, we developed a five category typology of collaborative working ranging from: modest exercises with shared services, through strategic alliances and joint ventures to alternative and cooperative organizational forms. This radical scenario does not assume a simple state/market binary. While for profit Universities are indeed growing in the sector, we can - and should - imagine alternative futures.

We then suggested that intriguing (if small scale) experiments with cooperative organizational forms are emerging. We consulted relevant organizations’ filing histories in Companies’ House and their websites to retrieve information in the public domain.

Organizational developments in the UK HE sector cannot be isolated from wider public sector reform ideas. The Cameron government (2010-2015)’s ‘Big Society’ narrative favoured mutualised and staff owned organizations, rather than either State or PLC based ownership. While it is unclear whether this narrative survived a wider post 2010 austerity drive, it supports third sector providers. The limited evidence we have suggests the mutualisation agenda progressed more rapidly in the local government and health and social care sectors than in HE, but relevant HE examples could usefully be identified and tracked.

The not for profit form is long established in such sectors as social housing and social care as an alternative to market and hierarchical governance. It typically produces a collective clan-like culture, a strong sense of mission and weak hierarchy. Some HE non profits are now emerging with DAP extensions: Regent’s University London is a not for profit provider governed by a Board of Trustees (rather than a Board of Directors). There are examples, too, of non-profit colleges operating online (considered below).

Another alternative form is the professional partnership where the organization is owned and managed by partners, usually senior professionals. Managers and non-executives at Board level (or what we term the Council in HE) are here weaker: power lies more with the partners. This form is apparent in other knowledge intensive sectors, including law and primary health care. The recently founded New University of the Humanities exhibits traits of a professional partnership form as its filing indicates senior academic staff have (small) equity stakes and its website indicates these some of the same people also manage the university.

The ‘virtual University’ uses powerful Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to change education provision radically. This theme is underexplored in the current HE literature. Examples include UK Arden University which offers online and blended learning programmes, and Capella in the USA. Different partners within HE networks are now collaborating within online alliances to deliver programmes jointly and electronically. The traditional university as a vertically integrated, physically present and hierarchical organisation shifts to a more ‘heterarchical’ and virtual network of allied organizations. Speed, flexibility and innovation become more important than the traditional search for scale and predictability, with scaling, in particular, not an issue for virtual organizations which are generally “global” at launch.

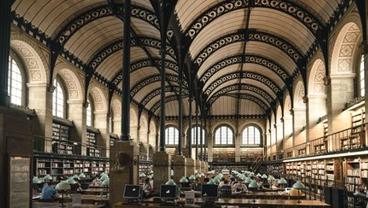

‘Social enterprises’ are mission driven organizations addressing unmet social needs, sometimes through radical and disruptive innovation (not favoured by cautious HE incumbents), often using new ICT technologies. Social enterprises are weakly developed in HE, but do exist. Founded in 2009, Peer2Peer University (P2PU) describes itself as a non-profit organisation that facilitates learning outside institutional walls and uses a virtual platform to facilitate face-to-face, peer-led learning, usually in public spaces such as libraries. Designing and leveraging open education tools and resources, P2PU offers a novel high-quality, low-cost, model for lifelong learning.

The Khan Academy is an American social enterprise providing free, high quality, high volume online education globally. It attracted major investments from such organizations as Google and the Gates Foundation and develops and delivers content in collaboration with the likes of NASA, MIT, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. We expect major philanthropists and charitable foundations, especially those connected to the high tech sector, to drive further online based HE innovation.

Within the UK, the Wellcome Trust is a major charitable funder that invests in developing science education and an ‘inspiring science’ programme, alongside its traditional base in biomedical research. Much funding is for work in schools, but possibly with HE spill-over.

In conclusion, the UK HE sector is undergoing significant organizationalchange. It can expect more M and A activity, but this response is by itself too limited and conventional. There is prima facie evidence of alternative organizational forms which transcend conventional public and private sectors alike. We should trace these intriguing organizational innovations as they evolve.

References

Ferlie, E. and Trenholm, S. (2017) ‘The Impact of Mergers. Acquisitions and Collaborations in Higher Education and Other Knowledge based Sectors: A Rapid Review of the Literature’, Research Report, London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education

Short bios

Ewan Ferlie is a Professor at King’s Business School and has written widely on large scale change in public services organizations, especially in the health and higher education sectors. Susan Trenholm is a lecturer at King’s Business School and has research interests in social entrepreneurship and social innovation.

Read the full report here.