11 May 2021

Lower exposure to PM2.5 can decrease behavioural problems in adolescents

Lower exposure to PM2.5 can decrease conduct problems in adolescents, new research has found.

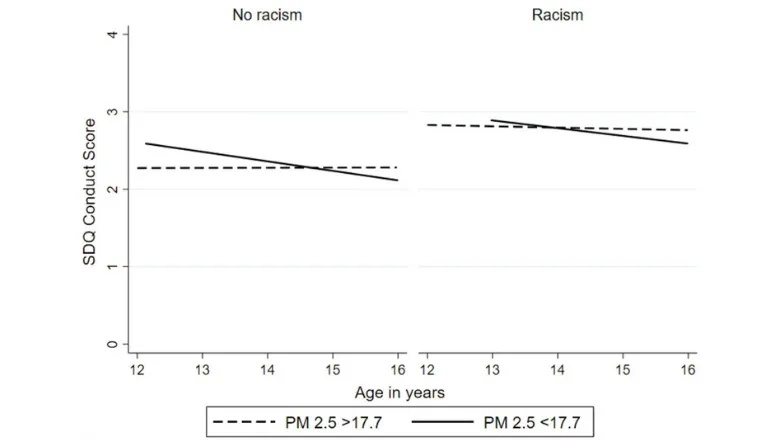

Furthermore, racism strengthened the effect of PM2.5 on conduct problems as they aged. At higher concentrations of PM2.5, this effect differed by ethnicity, with White British and Black Caribbean adolescents experiencing an increase in conduct problems with age.

The study published recently in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, by authors from King’s, Imperial College London, University College London, and Leeds Beckett university, explored for the first time in the UK the potential effect of exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 air pollution on the change in conduct problem symptoms for adolescents from different ethnicities.

A total of 4,775 participants from 2002-2003 (aged 11-13 years) to 2005-2006 (aged 14-16 years) were followed. Researchers had access to information about long-term exposure to air-pollution measured at their residential address. Adolescents completed questionnaires about conduct problem symptoms, experiences of racism, socio-economic and family circumstances, as well as health behaviours.

The study found that adolescents who were exposed to lower levels of PM2.5– which had a stronger link to change in conduct problems than NO2 – showed a decrease in behavioural problems.

The influence of PM2.5 exposure on conduct problems also differed among ethnicities. White British and Black Caribbean participants who were exposed to higher levels of PM2.5 showed an increase in their conduct problems compared to other ethnic groups. Other ethnic groups showed no change or slight decreases in the face of exposure to higher levels of PM2.5.

The study also showed that adolescents who reported experiencing racism also had higher conduct problems compared to adolescents who did not experience racism. This is because racism can elevate stress levels for a prolonged time which can in turn affect adolescent’s behaviour. As a result, the exposure to high levels of PM2.5 may be a ‘double whammy’ that exacerbates conduct problems.

Dr Alexis Karamanos, research associate from the School of Life Course Sciences at King's, said: “Conduct problems in adolescence can be markers for mental health problems, lower educational attainment and later criminality. Both racism and pollution can affect mental health. Our study has highlighted the importance of exploring how these environmental and social influences interact to better understand the development and protection of adolescents’ mental health”.

Professor Seeromanie Harding, Principal Investigator of the DASH study, also at King's, said: “DASH is a unique study because there are few cohorts with an ethnically diverse composition in adolescence. This is a sensitive time for the developing brain and when early signs of mental health problems begin to appear. The findings help us understand how growing up with systemic adversities can harm adolescents’ mental health”

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council, Chief Scientist Office, North Central London Research Consortium and Primary Care Research Network. The authors are grateful for the support received from many local communities who took part in the project.

Read the paper in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.