25 August 2020

How Covid-19 is revealing the impact of disinformation on society

New research from the King’s Centre for Strategic Communications in War Studies examines the causes and consequences of disinformation

The Covid-19 pandemic has provided new evidence of the impact of disinformation on people’s behaviour, according to a new report by researchers in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London. They also argue there has been too much focus on blaming social media for spreading false content, whist neglecting the spread of misleading content in traditional media by domestic political actors.

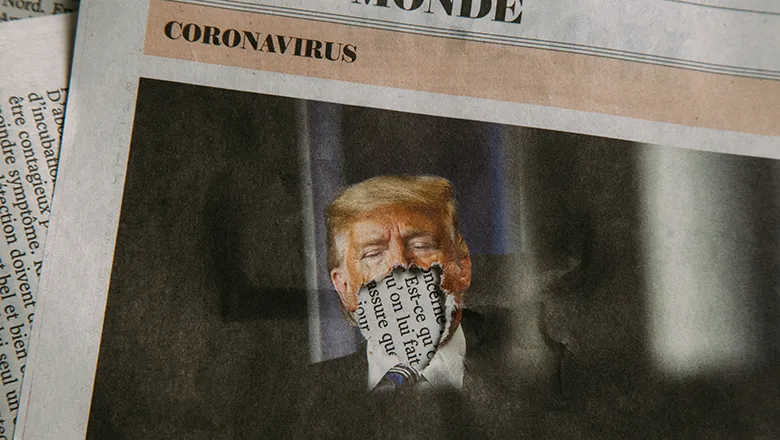

Disinformation is widely perceived as a significant threat to liberal democracies, with commentators blaming it for the election of Donald Trump, the Brexit vote, the rejection of climate science and the rise of anti-vaxxers. As part of a UK government research project with Ipsos MORI, Dr Thomas Colley led a team of researchers to look at the societal impact of disinformation in the UK. Using insights from the project, they conducted new analysis examining disinformation’s impact during the 2019 general election and the COVID-19 crisis.

Normally, it is difficult to prove the effect of a given message on an individual’s behaviour, but according to the researchers the pandemic has provided clearer measures of the impact of disinformation - the deliberate spread of false or misleading information, and misinformation - when false or misleading information is spread unintentionally.

The World Health Organisation early on declared that an ‘infodemic’ was taking place alongside the pandemic, following tragedies such as the 700 people in Iran who reportedly died of methanol poisoning because of misinformation that it could cure the virus. In the UK dozens of 5G phone masts were vandalised, after they were linked the spread of the virus. Ibuprofen sales declined and paracetamol sales increased after experts publicly questioned whether Ibuprofen was safe to treat symptoms.

Studying these examples, researchers are able to draw greater conclusions about the ways in which disinformation spreads through society. They argue that whether information even registers with people is mediated by their interest in it and trust in the source. Because of this, some disinformation may be better ignored, rather than amplifying its reach through additional media coverage.

Blaming social media ignores the importance of disinformation spread by domestic political actors and traditional media. Political leaders and even scientists in some countries have made misleading claims about supposed cures for Covid-19. The selective use of statistics – be it economic projections or illness and death rates – can mislead citizens too.

As Dr.Colley explains in an op-ed in the Independent, ‘Disinformation spreads through the interaction of many different information sources, not just social media. For British people, disinformation on social media may not even be the biggest issue. They overwhelmingly distrust social media news and rarely share it. Research shows they see disinformation from politicians and traditional media as more common and concerning.’

Dr Francesca Granelli, interviewed for the Independent, said:

“People are looking for information that reinforces their beliefs.

“Social media has been the focus [of anti-disinformation campaigns] but it’s not the sole area where people get news - it might be their friends, parents, newspapers, celebrities or musicians.

“It’s almost a perfect storm – the old gatekeepers have been removed and we haven’t found the right way to replace them.”

The researchers conclude that counter-disinformation policies focusing solely on social media, false content, and external actors will have limited impact given the greater significance in many cases of misleading content in traditional media spread by domestic political actors.

Going forward, the researchers hope that Covid-19 will generate a more nuanced and multidimensional approach to understanding and countering disinformation, recognising the wide range of actors that spread it, including politicians, journalists, scientists, social media influencers and ordinary citizens. They argue that further research is needed to examine how disinformation affects society, including social cohesion, and how it spreads offline between people, be it at the dinner table, in the pub, or at the school gate.