09 March 2021

Covid-19 and women's work: a global outlook

Dr Rose Cook, Senior Research Fellow at the King's Global Institute for Women's Leadership & Damian Grimshaw, Professor of Employment Studies at King's Business School

The pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities

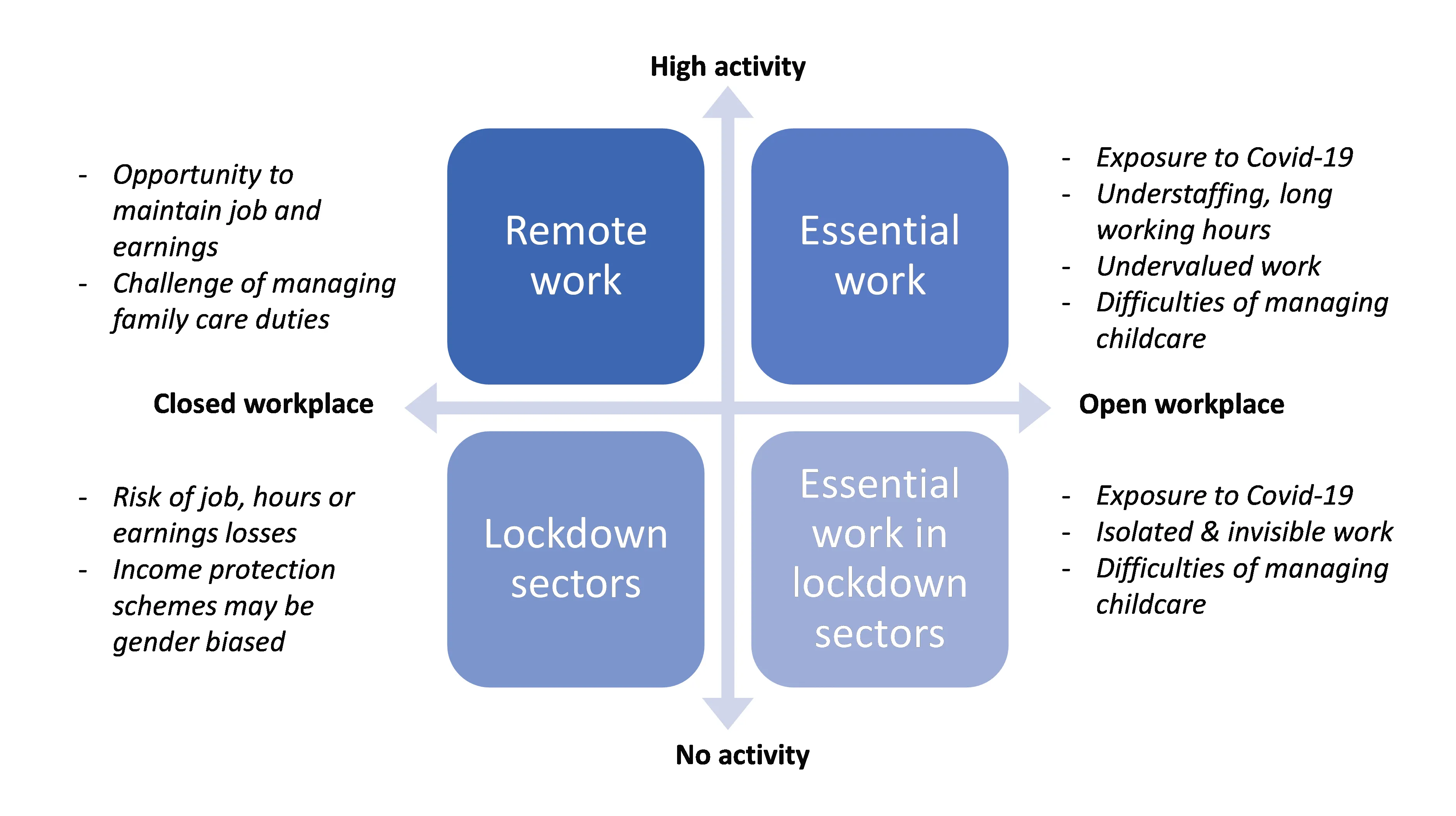

The Covid-19 pandemic and recession continues to exacerbate inequalities in women’s and men’s paid and unpaid work and risks reversing international progress towards gender equality. A useful way of thinking about the multiple and overlapping disadvantages faced by women is to separate out what has happened under Covid-19 into four distinct segments of work. Improved understanding about this ‘Gender Inequality Quartet’ can inform better designed policy and HR practices.

The core of essential work - around which everything else depends in this pandemic – is health and social care work where women account for more than seven in ten workers globally. Women face high exposure to Covid-19 in these jobs; illness and fatalities among healthcare workers are above average. The risk is higher for black, Asian and ethnic minority healthcare workers in the UK and the US, generating a double penalty for many women.

Healthcare workers around the world have protested about workplace safety, long working hours and understaffing, the lack of adequate protective equipment and limited mental health support. Added to this are longstanding complaints about inadequate wages in many countries. There were major strikes in India and South Africa last year and in the UK nursing unions are planning to strike for a wage increase in 2021.

Women also account for a disproportionately large share of jobs in lockdown sectors – those at most risk of being closed under lockdown measures, such as hospitality, retail, entertainment and personal services. Globally, women account for the majority of workers in arts and entertainment (61 percent) and accommodation and food services (54 percent), which have been especially hard hit. This means that many women’s jobs are at risk in the crisis. The disproportionate impact on women is not random. It reflects pre-crisis patterns of sex segregation that concentrate more women than men into low-wage service sectors, characterised by physical proximity to customers and other workers. Moreover, job protection schemes designed to protect workers’ jobs and incomes may be gender-blind or created with male workers in mind.

Among workers who retain work, there is evidence that women were disproportionately affected by cuts to working hours. In the United States, panel data analysis suggests mothers with young children reduced their hours four to five times more than fathers, increasing the gender gap in work hours by 20-50 percent.

Despite the clear protective benefits of remote work during the global pandemic, we now know it can have a detrimental effect on working mothers by exacerbating gender inequalities in unpaid domestic work. This raises wider questions post-Covid19 about how to promote both flexible working and gender equality. In many countries working mothers are doing more housework and childcare than before the pandemic– because of school and nursery closures and a lack of support from partners. A majority of mothers in the UK (and only a minority of fathers) who work from home report increased family stress and increased housework/childcare.

Some surveys suggest fathers working from home are now more likely to share housework (and who knows, this behaviour may endure for the long term). But the overall picture is that a far larger proportion of working mothers undertaking remote working are having to take on more cooking, cleaning, laundry and children’s schooling in addition to their paid work, increasing work-family conflict and putting at risk their mental health.

Finally, women face disadvantage resulting from the heightened isolation and invisibility of essential work in lockdown sectors. For example, cleaners have proven vital to keeping workplaces and consumer spaces free of Covid-19. The cleaning workforce is highly feminised in most countries and often includes a disproportionately high share of migrant workers. In the UK, cleaners have benefited from minimum wage rises, but most do not have the power to improve working conditions because of limited union representation. Also, the UK government decision not to classify cleaners in all sectors as ‘essential workers’ has created huge problems for many women.

The widening gap in work experiences between women and men is one of multiple inter-related fractures caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, given the centrality of women’s role in the world of work, actions to tackle the quartet of injustices faced by women will be essential to ensuring a more equal and decent world of work for all. As we move forward from the pandemic’s harsh exposure and exacerbation of historic inequalities, there is an opportunity to challenge the assumption that domestic and caring labour is women’s work and to reshape the distribution of paid and unpaid work for the benefit of all.

Further reading

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., et al. (2020) ‘How are mothers and fathers balancing work and family under lockdown?’

Chung, H., Seo, H., Forbes, S. and Birkett, H. (2020) ‘Working from home during the Covid-19 lockdown: Changing preferences and the future of work’.

Collins, Caitlyn, Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner, and William J. Scarborough. 'COVID‐19 and the gender gap in work hours.' Gender, Work & Organization (2020).

Cook, R. and Grimshaw, D. (2020). ‘A gendered lens on COVID-19 employment and social policies in Europe.’ European Societies, 1-13.

Nguyen, L.H., Drew, D.A., Graham, M.S., Joshi, A.D., Guo, C.G., Ma, W., Mehta, R.S., Warner, E.T., Sikavi, D.R., Lo, C.H. and Kwon, S. (2020). ‘Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community,’ The Lancet Public Health, 5(9), pp.e475-e483.

Rubery, J. and Tavora, I. (2021) ‘The Covid-19 crisis and gender equality’, in Social Policy in the EU, Brussels: ETUI.