01 October 2024

COMMENT: Wuthering Heights casting row: most adaptations struggle with picking the right Heathcliff and Cathy, but we deserve better in 2024

Dr Adelene Buckland, Reader in Nineteenth-Century Literature

How do you cast Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte’s 1847 novel about a child so brutalised by his adoptive family that he drives his pregnant love to death? Not, it would seem, like Emerald Fennell, the latest director to attempt it.

Fennell’s previous projects include the Oscar-winning A Promising Young Woman (2020) and Netflix hit Saltburn (2023), but she has been under fire for casting Jacob Elordi and Margot Robbie in the lead roles of Heathcliff and Catherine, two teenagers on the wild, 19th-century Yorkshire moors. As tanned Australian actors aged 27 and 34, best known for playing Elvis and Barbie, it is hard to imagine how they can pull this off.

But has anybody ever got Heathcliff and Catherine right?

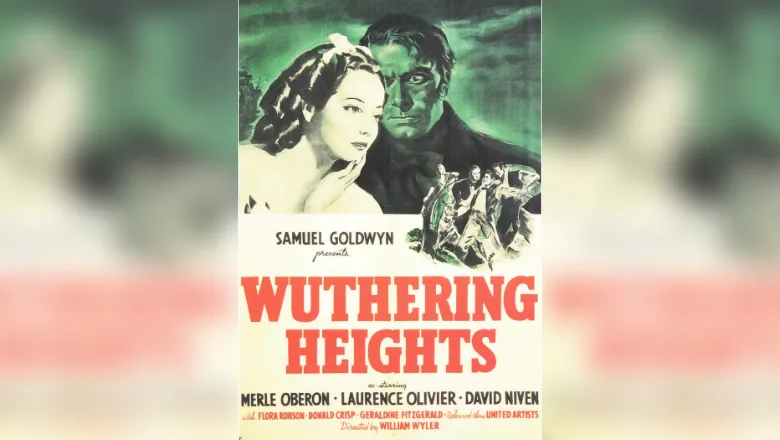

Lawrence Olivier was nominated for an Oscar for playing Heathcliff in 1939, but his clipped, Royal Shakespeare Company gentlemanliness hardly befitted the “savage vehemence” of the role. Heathcliff is an orphan, probably picked up on the Liverpool docks, bullied for looking like “a dark-skinned gypsy”, “a little Lascar, or an American or Spanish castaway” (a lascar was a sailor or militiaman often from Asia). Among his many eventual crimes, he tortures puppies and beats children. But the Olivier movie staged the novel as a classic Hollywood romance.

Until very recently other directors followed suit, cutting the story’s more brutal elements (including most of its second half) and casting dashing (white) leads like Timothy Dalton (1970) and then-newcomer Ralph Fiennes (1992). In the latter film, Juliette Binoche’s Catherine had a notably French accent. (Maybe best not to mention Cliff Richard’s 1996 musical, in which, at 56, he was panned for playing a teenage Heathcliff as a pop idol.)

As the director of a 2011 BBC Radio Three adaptation put it, Wuthering Heights is not supposed to be “a Vaseline-lensed experience”. But it has been mostly sold that way.

Perhaps the only director to capture the nightmarishness of Bronte’s text is Andrea Arnold, who in 2011 cast untrained actors in the central roles, including a black actor, James Howson, as Heathcliff. At the time, some critics even found that decision controversial. But the casting was a turning point, and Arnold’s bleak, almost wordless, adaptation changed the game.

In 2024, audiences are more aware that casting a white actor like Elordi as Heathcliff is not only to undersell the novel as romance, but to wilfully ignore the imperialism in the text.

There is evidence to suggest that Heathcliff’s story was at least partly inspired by a local slave-owning family, the Sills, who, as well as making their money from sugar plantations in Jamaica, had 30 enslaved Africans working on their home estate in Yorkshire.

Also, as mentioned, characters speculate about Heathcliff’s race throughout. For instance, Nelly Dean, Cathy’s family’s servant, wonders whether “[his] father was Emperor of China, and [his] mother an Indian queen.” He is clearly not white.

Still, in going in the opposite direction to Arnold, Fennell’s film might offer us something new.

The novel is difficult to film not only because it depicts human beings at their most primal, but also because it is so strangely told. Bronte rarely shows us Catherine or Heathcliff firsthand. We learn their tale through an uninitiated southerner, Lockwood, who himself hears much of the story from a servant with unreliable passions of her own.

Key scenes in the novel have an emotional realism drawn not only from the rough-hewn Yorkshire rocks but also from gothic melodrama: Catherine’s ghost literally bleeds as it grasps Lockwood through a window; Heathcliff digs up Catherine’s grave just “to have her in my arms again”. If this is realism, it is so extreme it borders on the theatrical.

And this is where Fennell excels. Saltburn’s bathtub scene is infamous for body horror, but mostly it depicts an urgent need to consume and be consumed by another. Saltburn also has its own graveside scene, which clearly echoes Heathcliff’s necrophiliac desires in Wuthering Heights.

I would argue there can be no justification for casting a white actor as Heathcliff, and it is to be hoped that Fennell rethinks this decision. But perhaps there is also something to be gained from having a Heathcliff and Catherine with the glitzy theatricality of Elvis and Barbie. Fennell isn’t going to give us the Catherine and Heathcliff we have come to expect, but it is possible she will evoke the passion the characters deserve.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article