06 August 2024

The cost of 'free' higher education: university number controls in Scotland

James Miller

The country's capped system for university places reflects a careful balancing act between financial sustainability, equity, and access

Professor James Miller is Principal and Vice-Chancellor of University of the West of Scotland.

Read the full essay collection in which this piece appears >

Background

The higher education system in Scotland is distinct within the United Kingdom due to the Scottish government’s totemic policy of providing free tuition for Scottish students. The quid pro quo being the number of places available is controlled (capped) to manage the financial impact.

HE number controls

The Scottish HE system is capped in the most obvious sense – a limit on the total number of funded places for (predominantly) undergraduate Scottish-domiciled students at Scottish universities, but the Scottish Funding Council (on behalf of the Scottish government) manages the funded student population in a number of further ways:

- Student number allocations per institution, allocated on a historical basis and with minor incremental adjustments.

- Allocations of funded places by ‘price group’, awarding places at six different price points to each institution, ostensibly aligned to cost of delivery.

- Specific ‘controlled’ populations, for typically public sector subjects such as nursing and teacher education.

- Targets for specific demographics as part of the conditions-of-grant Outcome Agreement agreed annually, including targets for widening participation, students articulating from college and students with care experience.

Tuition fees and grants

While the sector in Scotland is perceived not to have tuition fees, there are several ways that fees still play a role in the Scottish funding model. Scottish postgraduates (taught and research), some part-time, and students studying for multiple degrees, typically must pay a tuition fee – and are not part of the overall student number controls.

For the typical Scottish-domiciled undergraduate, the Scottish government funds the student tuition fees through the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS). SAAS in turn passes the fee (currently £1,820 a year) to the institution where the student is enrolled. Students do not repay this fee. This tuition fee level has not changed since 2009. The Scottish government also funds a grant, distributed to institutions via the Scottish Funding Council (SFC).

The level of grant is determined by the six price groups, with programmes allocated a price group. The price groups range from £3,781 to £15,940 per student, per year. This means expensive-to-deliver subjects such as medicine and veterinary medicine reach price group one, through intensive lab-based programmes such as physics, engineering in two, lab and complex programmes such as life sciences or education in price groups three and four, and classroom-based programmes of arts and humanities typically in price groups five and six. The fee element is demand-led and the grant element is capped.

In essence, universities can enrol as many Scottish-domiciled students as they wish. However, for any above the defined allocation they only attract the £1,820 per student fee, and if an institution exceeds 10 per cent above their population they are liable for penalties from the SFC of the full grant value per student.

There are some additional supplementary funding streams that are overseen by the SFC. These include the widening access and retention fund (£15.6m)[1]; compensation for expensive strategically important subjects (£6.2m); Small Specialist Institutions (£13.8m); and the Disabled Student Premium (£2.9m), all of which tend to be historic provisions that do not directly relate to the number of students and are often flat cash provisions and subject to removal, as was the case with an upskilling fund (£7m) and a pension support fund (£4.8m) in the 2024/25 allocations. Research and innovation funds are a separate stream, which have increased in recent years, however the SFC views these as offsetting some other reductions in the learning and teaching grants.

The funding is derived from a combination of the block grant received from Westminster via the Barnett formula and the additional revenue raised from the Scotland-specific income tax regime. A recent analysis demonstrated that funding per student received by institutions in Scotland is significantly lower than institutions in England, where number controls were removed some years ago and the fees became a liability for the individual student, repayable depending on circumstance (ie level of income). The same study also revealed that the cost to the Scottish government is significantly higher than in England:

“Per-student public investment in higher education in Scotland is approximately 5 times as high as in England. Despite this, higher education institutions in Scotland receive approximately 23% less funding per student than their counterparts in England. The public costs of the system and funding shortfall experienced by institutions has resulted in domestic student number controls, as well as an increasing reliance amongst higher education providers to recruit from the rest of the UK and overseas.”[2]

This policy, while designed to balance budget constraints and equitable access, has sparked considerable debate regarding its implications for students, universities, and the broader society in Scotland. The policy intent facilitates the very laudable principle that ability is the key determinant to accessing higher education in Scotland and not socioeconomic background.

This policy supports the Scottish government's commitment to “free education” for Scottish-domiciled students and forms part of what it describes as the social contract with the people of Scotland.[3] Until Brexit, this also applied to students from the European Union. This policy has never extended to rest of UK (rUK) students. As was sometimes quoted, a student from Umbria could study in Scotland for free, however a student from Northumbria had to pay a fee. There were also some very complex arrangements in place for students from Northern and the Republic of Ireland (liable for the r(UK) despite not being in the UK), especially for those holding dual passports.

Determining the cap

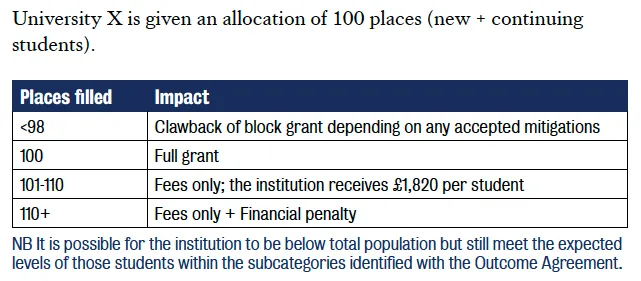

The funding made available to the SFC from the Scottish government as part of the annual budget setting process largely dictates the number of places available. Individual institutions are given their ‘allocated places’ and expected to manage within the tolerance of 2 per cent below and 10 per cent above the allocated number. Going beyond these thresholds leads to penalties or clawback of funding, by the SFC.

Illustrative case study

The core number can be traced back to its origins in 1992 and is largely rolled forward with some flexing between years. In the last 30 years there has been no zero-basing of the number and distribution of places across the 19 institutions in Scotland. There has been some change to where places are allocated within the price group structure – that too is now more than a decade ago. Given the history, combined with the current and expected fiscal constraints, there is a strong argument for a review of the mechanism, taking account of changing demographics, pedagogical practice and learning patterns.

There have been exceptional events where the number of places made available has shifted significantly. For example, the additional number of students meeting entry criteria when teacher-assessed grades were introduced during the Covid years resulted in an additional number of places being added to the system. Following Brexit, places once taken up by students from European countries remained in the system with the expectation that they would be filled by Scottish residents – in fact this has not been the case (largely for demographic reasons).

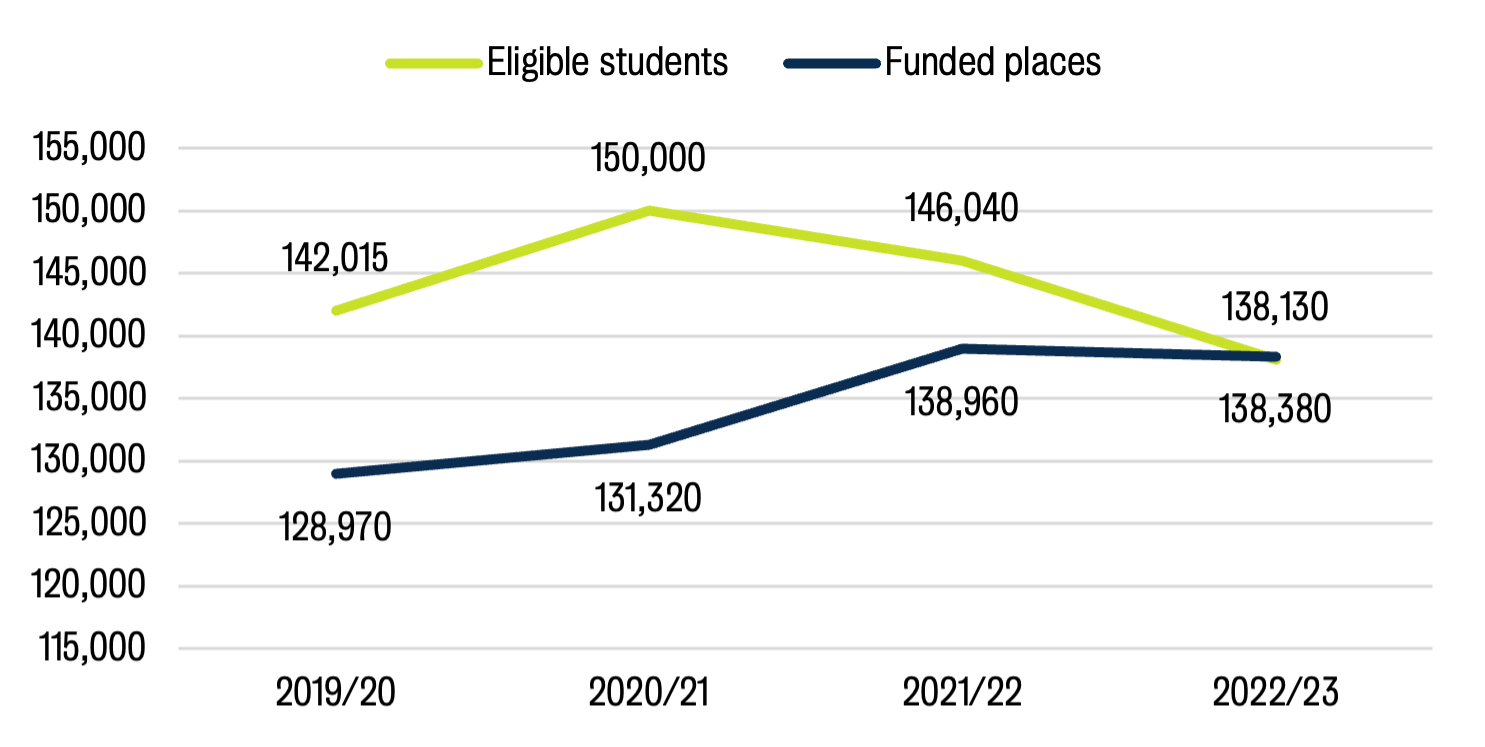

For some years the number of students eligible for funding has exceeded the number of places allocated by as much as 10 per cent, with the figures converging in very recent times. The chart below illustrates the gap.

In 2023/24 the number of allocated places dropped to 120,913 and will drop further to 119,540 in 2024/25. The number of eligible students for these years is not yet publicly available.[4][5]

Impact on students

While the policy aims to create a fair and sustainable system, it has several implications for students. The most immediate impact is on competition. With a limited number of places available, students potentially face intense competition to secure a place at their desired university in the location that they can attend if they are commuter-students, or within their desired subject

For students and those who advise them, the picture in Scotland can be confusing. The recent narrative from the Scottish government is that there are sufficient places available to everyone who meets the entry requirements in Scotland, while simultaneously students are hearing from their preferred institution(s) that places for Scottish students are full. This in turn gives rise to the view that Scottish students are being displaced for fee-paying international or rUK students, which provides an eye-catching headline but is not the case. Entry requirements vary between institutions and Scottish institutions have instigated an agreed programme of contextualised admissions as part of the approach to widening participation. As autonomous institutions, universities are of course free to accept any student.

The choices left open to students are:

- Another institution in Scotland which isn’t their preferred option.

- A different discipline.

- Paying for what they want to study in another part of the UK (or the world).

- Abandoning altogether the ambition of going to university.

Some of these choices and constraints also apply to students in a non-capped system where not every student is able to access their university of first choice. Similarly, some of these options are not viable for many applicants, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds due to financial constraints or other personal circumstances.

Impact on universities

Planning

The number control system presents both challenges and opportunities. In theory, it should provide a stable funding environment which aids planning. However, the reliance on government funding makes universities vulnerable to policy changes, political priorities and budget cuts, potentially impacting their long-term strategic planning and development. An annual budget settlement with an annual allocation of places for a group of students who expect to undertake a four-year undergraduate degree creates a complex environment in which to plan strategically and, where necessary, to implement immediate change. Turning off an undergraduate programme due to a reduced student population requires anything up to a three-year teach-out plan.

Changing the number of places and by extension the funding available to an institution on an annual basis makes medium- or long-term planning much more difficult and can disincentivise innovation within the sector. Conversely, reducing the funding (either directly or through flat cash settlements with rising costs) but retaining the number of places simply reduces the amount available per student.

In recent years, it also created difficulty for short-term planning. With annual Scottish government budgets not being prepared until December each year, the SFC is required to finalise and publish allocations for the next academic year in spring, which is very late in the university recruitment cycle.

Managing performance

There are further complexities within the allocation in that universities are expected to fill certain places with students with specific characteristics, defined by the institution’s Outcome Agreement. These include students from the most deprived areas of Scotland[6]; care experienced students; and articulating students from colleges with advanced standing. The consequences being that universities can find themselves adversely impacted by perturbations in other parts of the education system – the two most recent examples being teacher-assessed grades during Covid, which saw an increase in demand from schools, and a dramatic reduction in college students resulting in an equally dramatic drop in students articulating to university – with or without advanced standing. The drop in the college population was largely down to three factors: (1) a reduced number accepting college places during the Covid years, (2) a decrease in the completion rate, and (3) an increase in students entering the labour market rather than continuing to study at university, as a result of the cost of living crisis.

This latter drop resulted in several universities falling short of their allocated population. Where universities do not meet their allocated number, the funding council seeks to have the funding returned (clawback) and this retrospective correction can take up to two years following the allocation. As we look to the 24/25 academic year, the process for determining the clawback for academic year 22/23 has not begun. While the SFC seeks to understand the factors that have contributed to the under-population it does not necessarily take account of wider requirements as outlined in the Outcome Agreement. This is an issue that was highlighted some time ago by the Auditor General for Scotland:

“The SFC has recovered funding where universities have delivered less than the agreed volume of teaching activity. But there is no evidence of a direct link between funding and university performance against other agreed targets, such as those for student retention and for recruitment to courses in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).”[7]

This can lead to two contradictory situations: one, where an institution can meet its overall targets for student population, but failing to meet the specific targets within that, and two, where an institution meets the specific targets but fails to meet the overall population target

Full economic cost recovery

For some universities, the cap is, in one sense, a red herring – a level of funding that reflects the true cost of teaching is a more pressing concern. Audit Scotland in 2019[8] concluded that the sector on average only recovered 92 per cent of the full cost of teaching from publicly funded teaching. Across the UK, the recovery of full economic costs in 2022/23 has fallen to 90 per cent from 94 per cent in 2021/22.[9] Some institutions estimate recovery for Scottish-domiciled students could be as low as 50 to 60 per cent.[10] For some institutions, it does not make financial sense to seek to increase the number of Scottish-domiciled students, even where there is increased demand:

“At the margin, a Scottish university receives much more funding for teaching an additional rUK or international student than an additional Scottish student. This means Scottish universities have a financial incentive to expand provision, but not for Scottish students.”[11]

Impact on society

The capped system has broader implications for society. A capped system can influence the alignment of higher education outputs with labour market needs. This is most evident in Scotland by the defined controlled subjects – including health-related professions (medicine, nursing, paramedics and professions allied to medicine), as well as both primary and secondary teaching. These are directly controlled by the relevant Scottish government directorates and are influenced by the workforce planning data generated from the National Health Service and the education sectors. Once identified, this workforce data forms the basis of places allocated to individual institutions providing such programmes.

By regulating the number of graduates in various professions, the government can better match the supply of skilled workers with demand, potentially reducing unemployment among graduates. However, this requires precise forecasting and coordination, which has been challenging across several years.

More cynically, it might be suggested that where there are identified workforce shortages it becomes the universities’ problem to recruit more and thus overlooks issues such as retention of nurses/teachers/doctors, lack of willingness to live in specific parts of country, or a lack of appeal in, for example, STEM teaching.

There are few examples from around the world where the workforce planning process has neatly matched the creation of suitably qualified graduates, which is an artefact of many different factors including economic stability, public sector pay constraints and demographic changes.

What next?

The capped system for university places in Scotland reflects a careful balancing act between financial sustainability, equity, and access. The policy objectives of balancing sustainable financing and high standards of education are in some peril. As the funding levels fall, not only in absolute terms but in relation to competitor nations, there is an inevitable consequential impact on the quality of the student experience and the relative standing and reputation of the nation’s higher education.

To date, these funding gaps have been filled through the innovation and entrepreneurial endeavours of universities. However, one of the most important additional streams of funding, international student recruitment, has been severely negatively impacted by immigration policy, a reserved matter for the Westminster government.

An approach that incorporates funding commensurate with cost of delivery – which might include the need for a different funding model that does not necessarily move away from the principle of free tuition, and that also reflects flexible learning options – can help address the challenges and maximise the benefits of this policy. There will always be the need and indeed desire for universities to exercise their entrepreneurial muscle to diversify income opportunities. Through continuous evaluation and adaptation, Scotland can maintain its commitment to accessible and high-quality higher education while meeting the evolving needs of its population and economy.

[1] The data for these funding streams is for 2024/25.

[2] London Economics. (2024). Examination of higher education fees and funding in Scotland [Policy note]. https://londoneconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/LE-Nuffield-Foundation-HE-fees-and-funding-in-Scotland-FINAL.pdf

[3] Scottish Government. (2023, February 20). A social contract with Scotland. https://www.gov.scot/news/a-social-contract-with-scotland/

[4] Scottish Funding Council. (2023). Students eligible for funding 2022-23, p. 16. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploadedFiles/Students_Eligible_for_Funding_2022-23.pdf

[5] Scottish Funding Council (2024). University Final Funding Allocations 2024-25. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/publications/university-final-funding-allocations-2024-25/

[6] Using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), universities are expected to recruit 20 per cent of their undergraduate population from 20 per cent of the most deprived areas of Scotland.

[7] Audit Scotland. (2019). Finances of Scottish universities, p. 5. https://audit.scot/uploads/docs/report/2019/nr_190919_finances_universities.pdf

[8] Ibid., p. 16.

[9] Office for Students. (2024). Annual TRAC 2022-23: Sector summary and analysis by TRAC peer group. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/annual-trac-2022-23/

[10] Private communication.

[11] Ogden, K., & Thomas, M. (2024). Scottish Budget: Higher education spending, Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/publications/scottish-budget-higher-education-spending