This assignment encourages students to see the relevance of what they learn in the classroom to interpret the world around them outside of the classroom. I designed the assignment for them to feel they have new tools to appraise the space around them critically. The task allows students to take a break from their laptop, go outdoor for a walk, and experience the city creatively, through a new medium.

Dr Sara Marzagora, Senior Lecturer in Comparative Literature

09 April 2025

Student photography competition challenges concept of British nation

Comparative Literature BA students captured images representing different perspectives on the British nation for a photography competition.

Dr Sara Marzagora, Senior Lecturer in Comparative Literature in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, challenged students to apply Edward Said’s contrapuntal method to the public spaces of London.

Said’s approach encourages consideration of both the coloniser and the colonised in analysing literature. This sits in contrast to the way British novels can devalue ‘other worlds’ in favour of ideas of the British nation and its language, and how they often fail in preventing or opposing imperialist domination. The thoughts, lives and labour of colonised people end up erased, inviting us to consider an alternative approach to literary criticism – reading canonical texts through the erasures and silencing they enact.

We must take into account both processes, that of imperialism and that of resistance to it, which can be done by extending our reading of the texts to include what was once forcibly excluded.

Edward Said

Dr Marzagora asked students to apply this methodology to reading London as an ‘urban text’, taking photographs representing how colonialism is and is not visible, and what is hidden in between.

Students interrogated how the city tells stories through statues, monuments, plaques, flags, posters, graffiti, murals, street signs and more. They considered who is excluded from the official image of the British nation, what stories have been hidden and silenced in the way the British nation spatially presents itself, and how photography can capture these absences.

View the winning photos below and see all entries here.

Tulsi Raja (winner)

'Originally designed for royalty, Kew Gardens evolved into a nationalist botanical garden in 1840, becoming a space to classify and control nature through a Victorian lens. This transition embodies environmental orientalism, where nature is dominated by humans and cultural stereotypes are reinforced. One of the most telling examples of Kew’s role in colonialism is its involvement in bioprospecting, particularly in the rubber trade. Kew facilitated the illegal smuggling of rubber seeds from Brazil. These seeds were then planted in Kew’s greenhouses and then transported to British colonies for large-scale rubber production. This act undermined local industries in Brazil and enabled Britain to establish an extremely profitable rubber production. This exploitation highlights the economic botany approach of that time, whereby nature was primarily seen as a resource for profit.

The Palm House, built to contain exotic plants, symbolises human dominance over nature. This division between the Palm House that showcased the exotic and the traditional rose gardens right next to the greenhouse emphasises the ‘us’ versus ‘other’ dynamic. In keeping these plants it served as an important asset in turning botanical knowledge into another assertion of power for the empire. Kew’s emphasis on British scientific accuracy and British aesthetic reflects the colonial outlook, the combination of science and arts suggests a desire to curate a natural world aligning with British sensibilities.

This photo is taken from the outside of Palm House, showing both the inside full of exotic plants and the reflection of the Botanical restaurant directly opposite. The restaurant building was originally a museum that housed Kew’s economic botany collections (now moved to another building). A collection of artifacts that derive from plants, taken from around the world, demonstrated the success of Imperial expansion, and exploration. This collection should be translated and examined with its exploitation of resources in the colonies.'

Georgia Ho (runner-up)

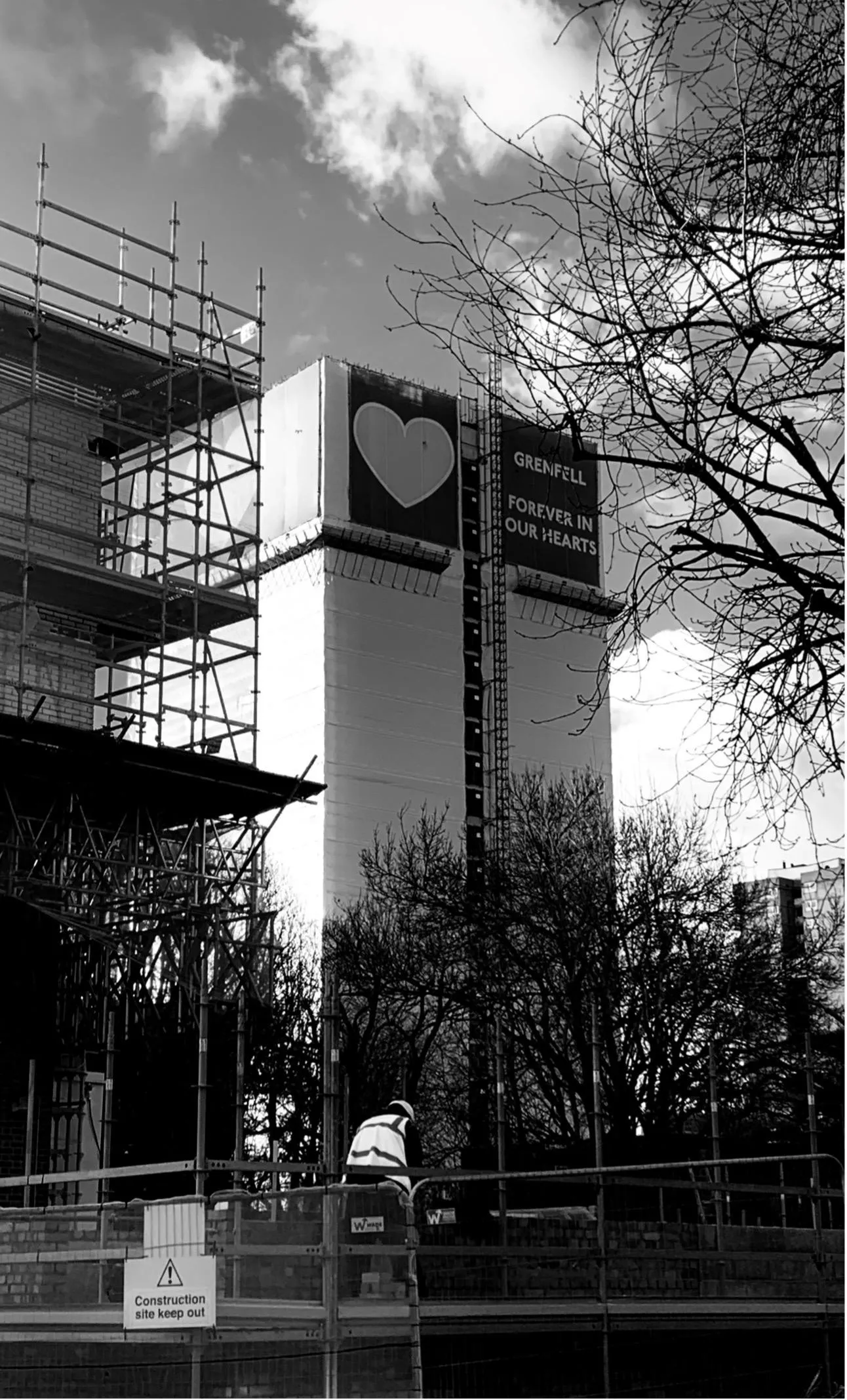

'In keeping with Edward Said’s method of contrapuntal reading, we are asked to question who has been written out of the nation, wherein the landscape of London can be treated as a text. In the foreground of this photograph stands a builder, working on new housing, a glance of London as modern, ever-growing, supposedly housing increasing populations as it soars into the future. But the counterpoint is always present, once we choose to observe it – in the background stands what remains of Grenfell Tower, covered in plastic sheeting, marked by ‘Forever In Our Hearts’. The majority of the 72 lives lost in Grenfell in 2017 were of immigrant families, many of them children and the disabled. Despite frequent complaints to Kensington and Chelsea Council, one of the wealthiest boroughs in the country, about the fire risk of their building, residents were ignored for years. The later inquiry deemed their deaths preventable, and the result of years of failings; of deliberate dishonesty from the cladding manufacturers, negligence from outsourced fire safety inspectors, total ignorance from the council’s housing management team, and failings of successive governments to properly legislate on building safety. Emails uncovered as part of the inquiry revealed that the cladding producers described their own product as ‘burning like paper’, and were warned that it had ‘the same fuel power as a 19,000 litre truck of oil’, with the potential to kill ’60 to 70 people’, and yet this was kept confidential. And part of the purpose of this cladding was purely aesthetic - in the wealthy Kensington and Chelsea borough, with a new leisure centre next-door, the council wished to renovate the tower block in order to fit its surroundings, inconsiderate of the safety of its generally lower-income residents. Conservative politician Jacob Rees-Mogg, when asked if the tragedy had any relation to race or class, not only denied this, but went further to suggest that the victims lacked ‘common sense’ in not ignoring the advice of the London Fire Brigade, and staying within their homes.

The point and counterpoint here are remarkably visible. The primary telling of the city stands in the foreground, of a developing, modern, accessible place, open for new residents, here situated in famously wealthy Kensington, an iconic image of London, expressed in all its landmarks and the film Notting Hill, as just one example. But the counterpoint can never be removed, not fully – Grenfell Tower looms behind, reminding us of the 72 lives lost who, unless memorialised in this way, would not have made up part of the quintessential Kensington/London/Britain image, due solely to race and social class, and their residence in council housing. Their total neglect, and the failings of the many institutions that were supposed to protect them, cannot be forgotten; an effort must be made to keep their stories, all the more at risk after the recent government decision to demolish the building entirely.'