This ground-breaking study has evaluated the potential role of bacteriophages - viruses that specifically kill populations of bacteria in the gut - to beneficially change the gut microbiome in alcohol-related disease. The study team has shown that bacteriophages can specifically target cytolytic E. faecalis, providing a method to precisely edit the gut microbiome and offering a new treatment method for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. This novel approach now needs to be expanded to be tested in human clinical trials

Professor Debbie Shawcross

13 November 2019

Phage therapy shows promise for treating Alcoholic Liver Disease

Study shows treating mice with bacteriophages clears bacteria and eliminates the disease in mice.

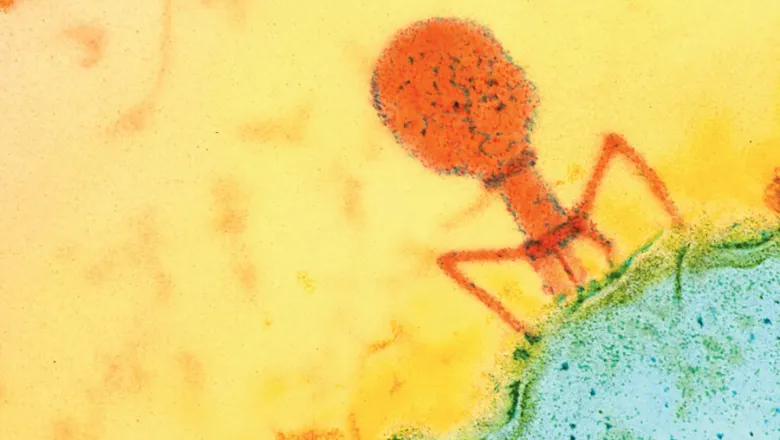

A team of researchers led by King’s College London and the University of California San Diego School of Medicine have for the first time successfully applied bacteriophage (phage) therapy in mice to alcohol-related liver disease. Phages are viruses that specifically destroy bacteria.

In a paper published today in Nature, the team discovered that patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis had high numbers of a destructive gut bacterium and that they were able to use a precise cocktail of phages to target and kill the bacteria, eradicating the disease.

They found that with this disease, liver cells are injured by a toxin called cytolysin, secreted by Enterococcus faecalis, a type of bacteria typically found in low numbers in the healthy human gut. They found that people with alcoholic hepatitis have more cytolysin-producing E. faecalis in their guts than healthy people. The more E. faecalis present, the more severe their liver disease.

Using samples collected from patients, the researchers found that nearly 90 percent of cytolysin-positive patients with alcoholic hepatitis died within 180 days of hospital admission, compared to approximately 4 percent of cytolysin-negative patients.

To investigate the potential for phage therapy, the researchers isolated four different phages that specifically target cytolysin-producing E. faecalis. When they treated the mice with these, the bacteria were eradicated, and alcohol-induced liver disease was abolished. Control phages that target other bacteria or non-cytolytic E. faecalis had no effect.

Professor Debbie Shawcross, Professor of Hepatology and Chronic Liver Failure at King’s College London said: “Chronic liver disease is responsible for 1.2 million deaths worldwide. It is the third biggest cause of premature mortality and lost working life behind heart disease and self-harm. In the UK, most people die from alcohol-related liver disease at a young age, with 90% under 70 years old and more than 1 in 10 in their 40’s."

Currently, severe alcoholic hepatitis is most commonly treated with corticosteroids, but they don’t tend to be effective. Early liver transplantation is the only cure but is only offered at selected medical centres to a limited number of patients.

With the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections, researchers have turned their attention to developing phage therapy. In limited cases, patients with life-threatening multidrug-resistant bacterial infections have been successfully treated with experimental phage therapy after all other alternatives were exhausted.

This novel avenue of research now needs to be expanded to test the safety and effectiveness of phage therapy in human clinical trials in patients with the alcohol-related disease. It is also likely that other forms of chronic liver disease associated with changes in the gut microbiome will also benefit from this novel approach, such as fatty liver disease.

Professor Debbie Shawcross