Using the most advanced cryo-electron microscopes, we were able to determine the atomic structure of this protein, demonstrating that instead of a filament, it forms a rigid tube, with a hollow cavity at its centre. This is strikingly different from actin, or any of its other bacterial counterparts.

Dr Julien Bergeron, Senior Lecturer in the Randall Centre for Cell & Molecular Biophysics at King’s

14 March 2025

Newly identified bacterial protein to help with design of cancer drug delivery system

Researchers have identified a previously unknown bacterial protein, the structure of which is being used in the design of protein nanoparticles for the targeted delivery of anticancer drugs to tumours.

A previously unknown protein in a family of bacteria found in soil and the human gut microbiome has been discovered – which could help drug delivery in cancer treatment.

In a paper published in PNAS, researchers at King’s College London and the University of Washington describe the unique 3D structure of this protein, which is now being used to develop cancer drug delivery systems that can target drugs to tumour sites.

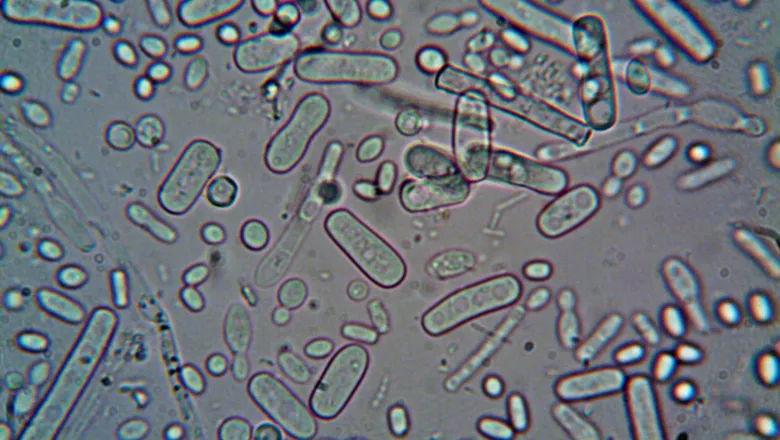

The bacterial protein identified by the team, which they have named BeeR, has a similar function to actin – the most abundant protein in the majority of human cells. In the presence of a chemical called ATP, actin molecules can join together into long spiral chains known as filaments. The filaments sit in the outer membrane of cells and have many important functions, including helping cells to maintain their shape, divide and move. Actin can also break down ATP, which triggers the filaments to disassemble.

Bacteria have similar proteins to actin that form filaments in the presence of ATP and help to control cell shape and division. But when studying BeeR, the researchers discovered one striking difference to other actin-like bacterial proteins – its structure.

Dr Julien Bergeron, Senior Lecturer in the Randall Centre for Cell & Molecular Biophysics at King’s, who led the research, said: “We used metagenomics data – extensive sequencing of bacterial genomes from the environment – to identify a previously unknown actin-like protein in a family of bacteria known as Verrucomicrobiota."

Dr Bergeron first discovered the protein when he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle in the lab of Professor Justin Kollman, senior author of the paper. But, at the time, they were unable to solve the structure of the protein.

After moving to King’s and studying the protein using advanced imaging techniques, Dr Bergeron – with the help of lab group members Shamar Lale-Farjat, Hanna Lewicka and Chloe Parry – found that in the presence of ATP, BeeR assembles into three stands that form a hollow, tubular structure.

“At this time, we don’t know the function of BeeR,” adds Dr Bergeron. “Nonetheless, the identification of an actin-like protein forming a tubular structure transforms our understanding of the evolution of this critically important family of proteins.”

Through his spin-out company Prosemble, Dr Bergeron is now working to exploit the unique structure of the hollow BeeR tubes to create protein nanoparticles for the targeted delivery of anticancer drugs to tumour sites. The team is currently testing the approach in pre-clinical breast cancer models.

Not only are the BeeR structures tubular, but they also have a cavity at their centre that is big enough to contain drug molecules. Since we can easily control the assembly and disassembly of the tube with ATP, it gives us a simple method to deliver and release the drugs at the desired location.

Dr Bergeron

The work was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Human Frontier Science Program and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.