11 April 2019

Mice reveal 38 new genes involved in hearing loss

New research from King's College London and Wellcome Sanger Institute has revealed multiple new genes involved in hearing loss.

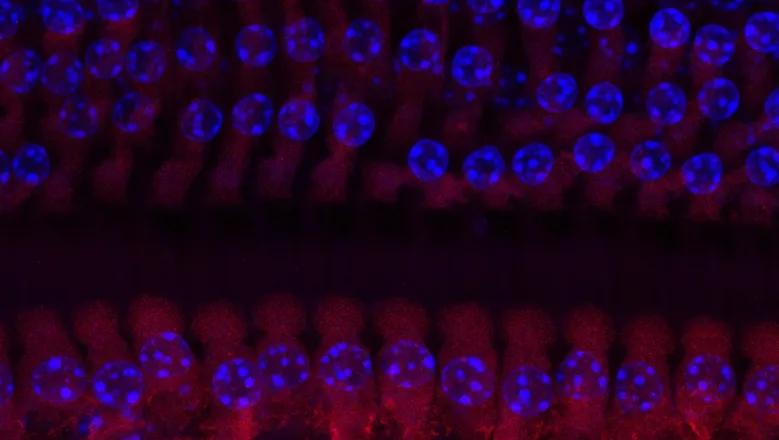

Researchers at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience carried out a large-scale screen of 1,211 mice with genetic mutations, identifying 38 genes that had not previously been suspected to be involved in hearing. The new genes identified reveal metabolic pathways and regulatory processes involved in hearing and provide a rich source of therapeutic targets for the restoration of hearing.

Progressive hearing loss with age is extremely common in the population, leading to difficulties in understanding speech, increased social isolation and associated depression. It has significant heritability, but so far very little is known about the molecular pathways leading to adult-onset hearing loss, hampering the development of treatments.

Professor Karen Steel, at the Wolfson Centre for Age-Related Diseases, and colleagues took a genetic approach to identifying new molecules involved in hearing loss by screening a large cohort of newly generated mouse mutants using a sensitive electrophysiological test, the auditory brainstem response.

Some of these genes reveal molecular pathways that may be useful targets for drug development. Eleven were found to be significantly associated with auditory function in the human population, and one gene, SPNS2, was associated with childhood deafness, emphasizing the value of the mouse for identifying genes and mechanisms underlying complex processes such as hearing.

Further analysis of the genes identified and the varied pathological mechanisms within the ear resulting from the mutations suggests that hearing loss is an extremely heterogeneous disorder and may involve as many as 1,000 genes. According to the authors, the findings suggest that therapies may need to be directed at common molecular pathways involved in deafness rather than individual genes or mutations.

Professor Steel said: ‘Most of the genes that we already know to be involved in deafness were found because of severe effects during the development of hearing, but in our study we looked for more subtle effects and detected several mouse lines with normal development but later deterioration of hearing.’

‘Some of the genes we identified are needed for ongoing maintenance but not for normal development of hearing in mice, and some genes show genetic variants associated with auditory function in the UK adult population. Our next step is to find out if we can manipulate the molecular pathways involved to slow down or stop the progression of hearing loss.’

The study, published in PLOS Biology, is available online.