14 February 2023

London's poverty rate is shockingly and stubbornly high

Rebecca Roberts

The Policy Institute is uncovering how the cost of living crisis is affecting London against a backdrop of high rates of persistent poverty

The Policy Institute at King’s College London recently ran a series of deliberative workshops with citizens from Lambeth, Southwark and the City of Westminster about the cost of living crisis, and the policy responses they wanted to see.

As part of this process, we presented participants with a range of credible, expert information about the issues at hand to help them make their decisions about the changes they wanted to see. One of our experts was Rebecca Roberts, Grant Manager at the Trust for London, which tackles poverty and inequality in the capital through grant-making and social investment. She writes for us below.

****

For the last 20 years, London has consistently had the highest rate of poverty in the UK. This fact often seems to surprise people – even those that live there. The wealth and grandeur portrayed in the media and popular culture obscures the extreme levels of hardship that many Londoners face.

This was the case before the pandemic and now as the cost of living crisis bites. For millions of Londoners, their day-to-day experience was already shaped by high housing costs, low-quality homes and extortionate childcare, as well as low-pay and poor working conditions. Now, they are confronted with rising living costs, stagnating wages, and deepening poverty. Rather than a new crisis, many are facing an intensification of existing struggles.

Our core mission at Trust for London is to support communities and organisations working to tackle poverty and inequality. We do this by funding frontline advice work, advocacy and people-powered campaigns, across housing justice, employment, migrant rights, social security and living standards. We also fund research on poverty and publish London’s Poverty Profile, a regularly updated online resource sharing data to help us better understand the nature of poverty in the capital.

Insights and data from the LPP and other research reveal the hardship people were experiencing before and during the pandemic – and what they’re dealing with as the cost of living crisis unfolds.

The highest rate of poverty in the UK

According to analysis from the Social Metrics Commission (SMC), around 2.5 million Londoners are in poverty. That means they struggling to make ends meet, secure good-quality affordable housing, or tie down the decent work they need to rise above the poverty line.[1]

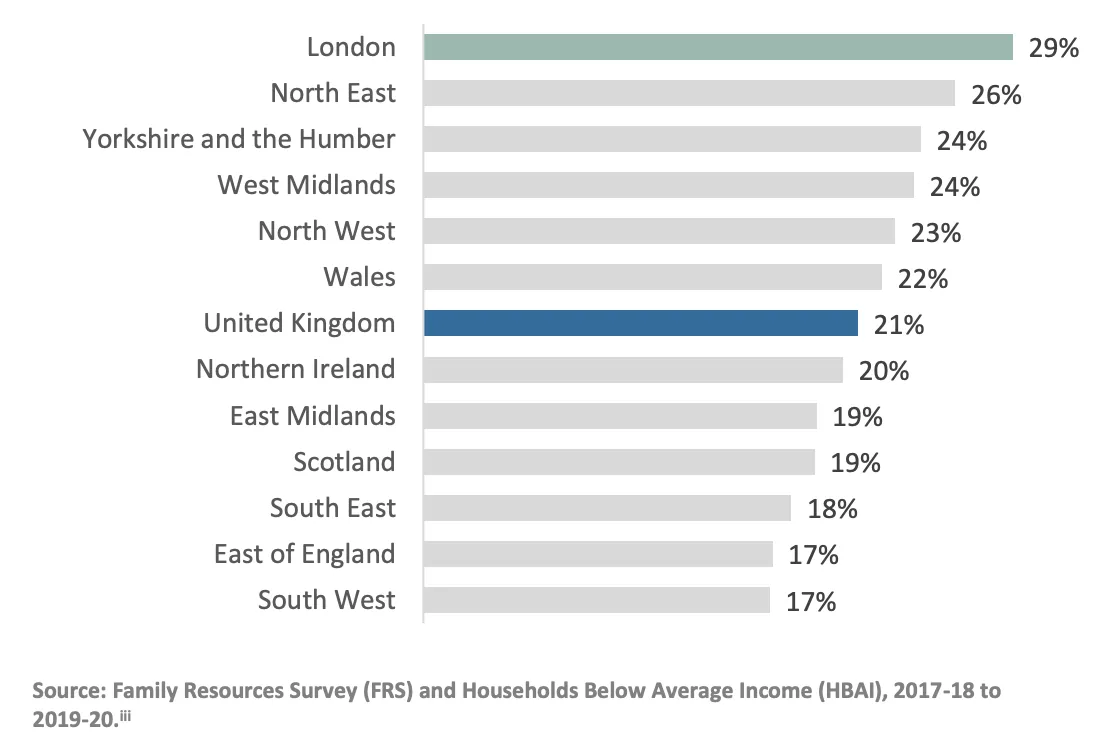

The graph below, from the Legatum Institute, shows that in the year before the pandemic, 29% of Londoners (almost one in three) were defined as being “in poverty”, compared to the UK average of 21%. When looking at this over time, we see that poverty has remained fairly stable but stubbornly high.

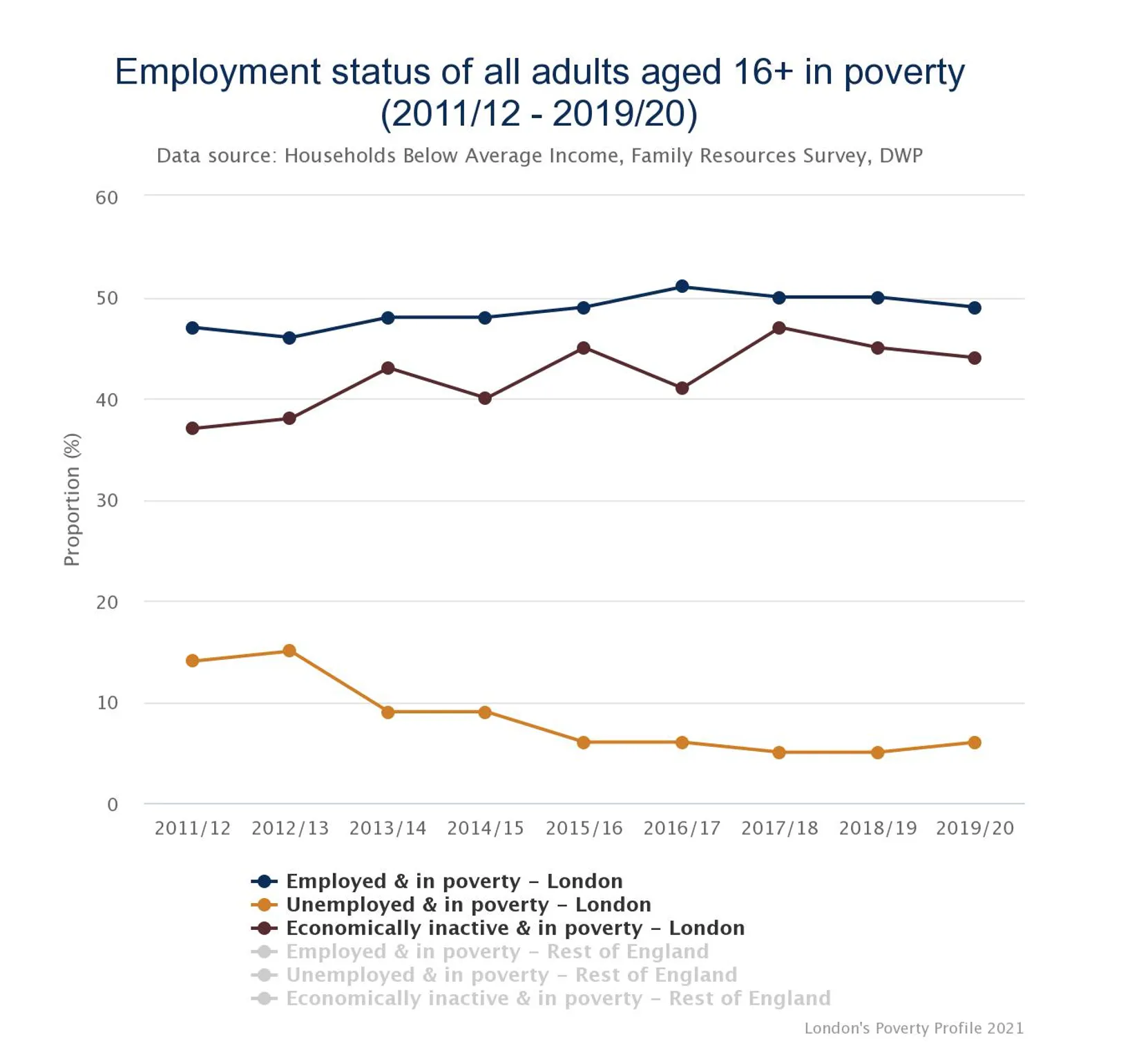

Londoners are also more likely to experience particularly severe forms of poverty. Deep poverty refers to someone living more than 50% below the poverty line. Persistent poverty means that someone has been experiencing hardship for a number of years. It is also the case that Londoners in poverty are more likely to be in work than the rest of the country.

It is worth mentioning that new research published in January by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation suggests the North East of England, with a poverty rate of 26%, may have just crept above London at 25%. Slight differences in the way that the JRF has evaluated the data compared to the Social Metrics Commission means that the measurements of poverty rates vary. There is some work to be done to understand how the two compare, but the fact remains that poverty in the capital is shockingly and stubbornly high.

Who is in poverty?

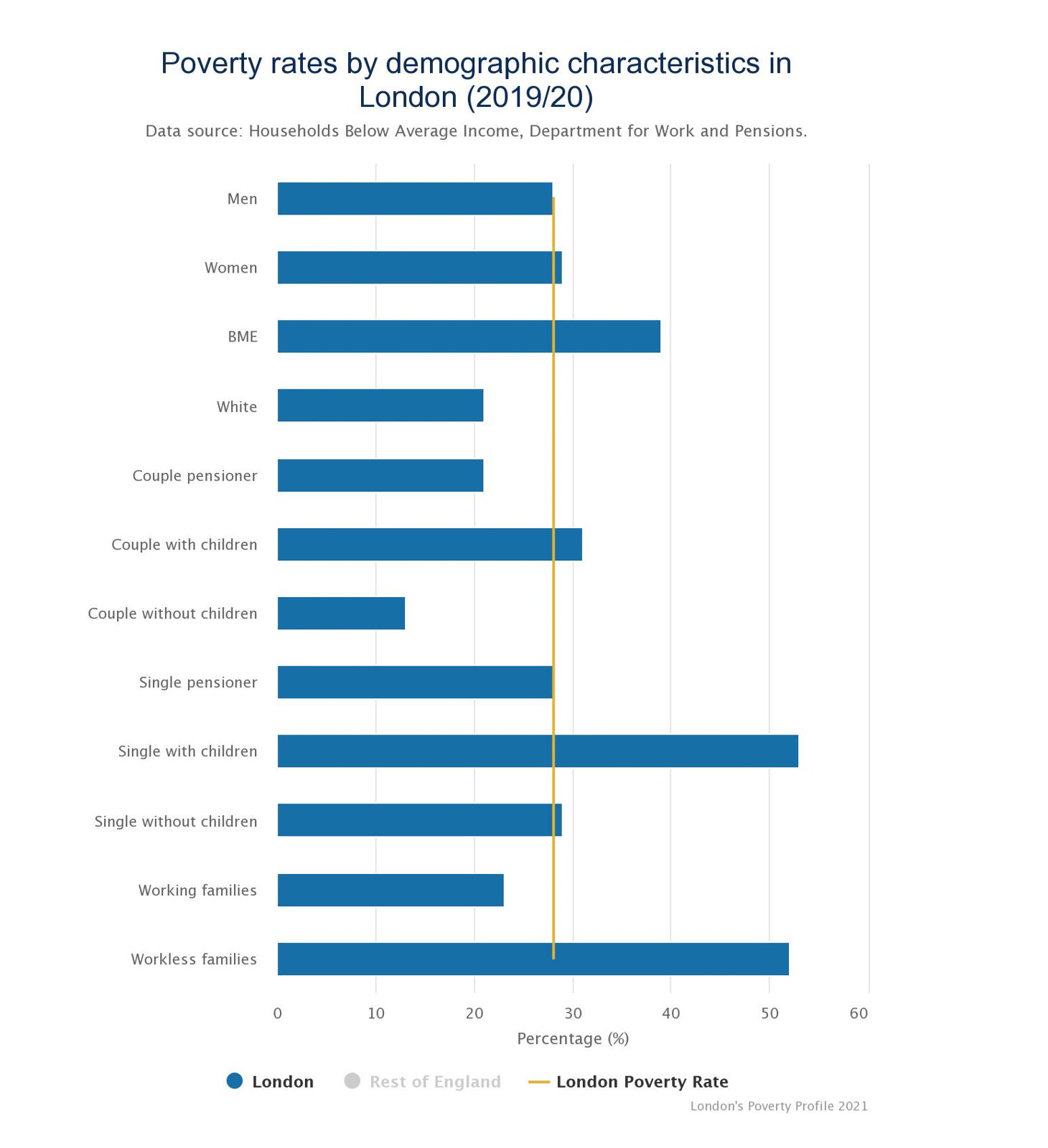

The majority of households in poverty in London are families headed by a non-white person (56%). In London 38% of those in households with a disabled person are in poverty – that’s significantly higher than in the rest of the UK (26%).

Throughout the UK, children face a higher poverty rate than working age adults and pensioners. The child poverty rate in London is 42% – that’s two in five – and significantly higher than the 31% rate in the rest of the UK.

High housing and childcare costs are key drivers of poverty

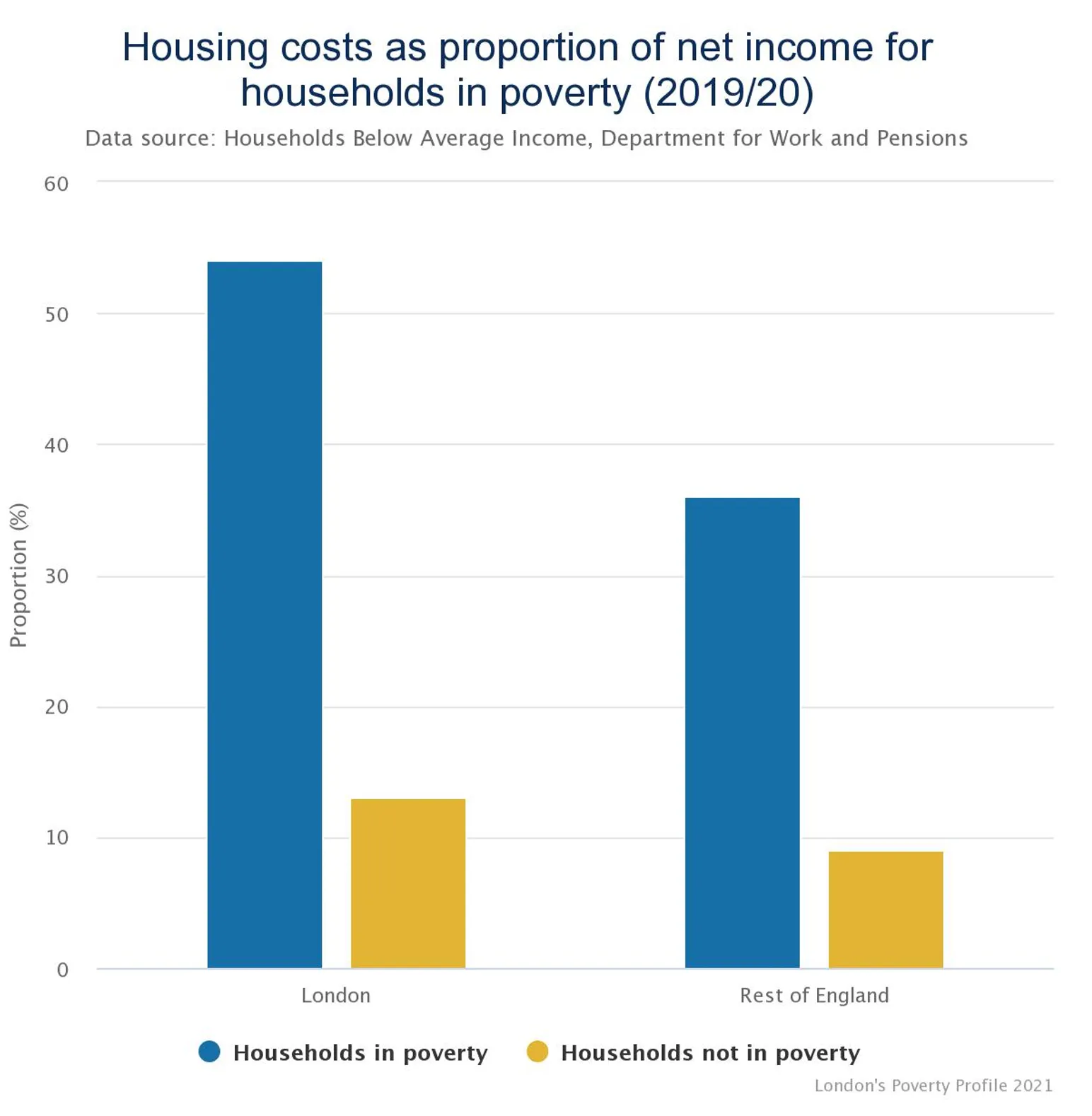

We also know that families in poverty in London spend 51% of their income on housing costs (compared to the national average of 39%). For those living in private rentals in London, this rises to 64% of a family’s income. The latest data on rental costs in London showed a 14.5% increase in just one year.

While political debate often focuses on the need to build more homes, some are now asking questions about whether the problem is actually rooted in the lack of affordable and good-quality homes as opposed to quantity. Action on Empty Homes report that in 2022 there were 34,000 long-term empty homes in London, which if you include empty second homes, rises to 80,000 and has been increasing each year.

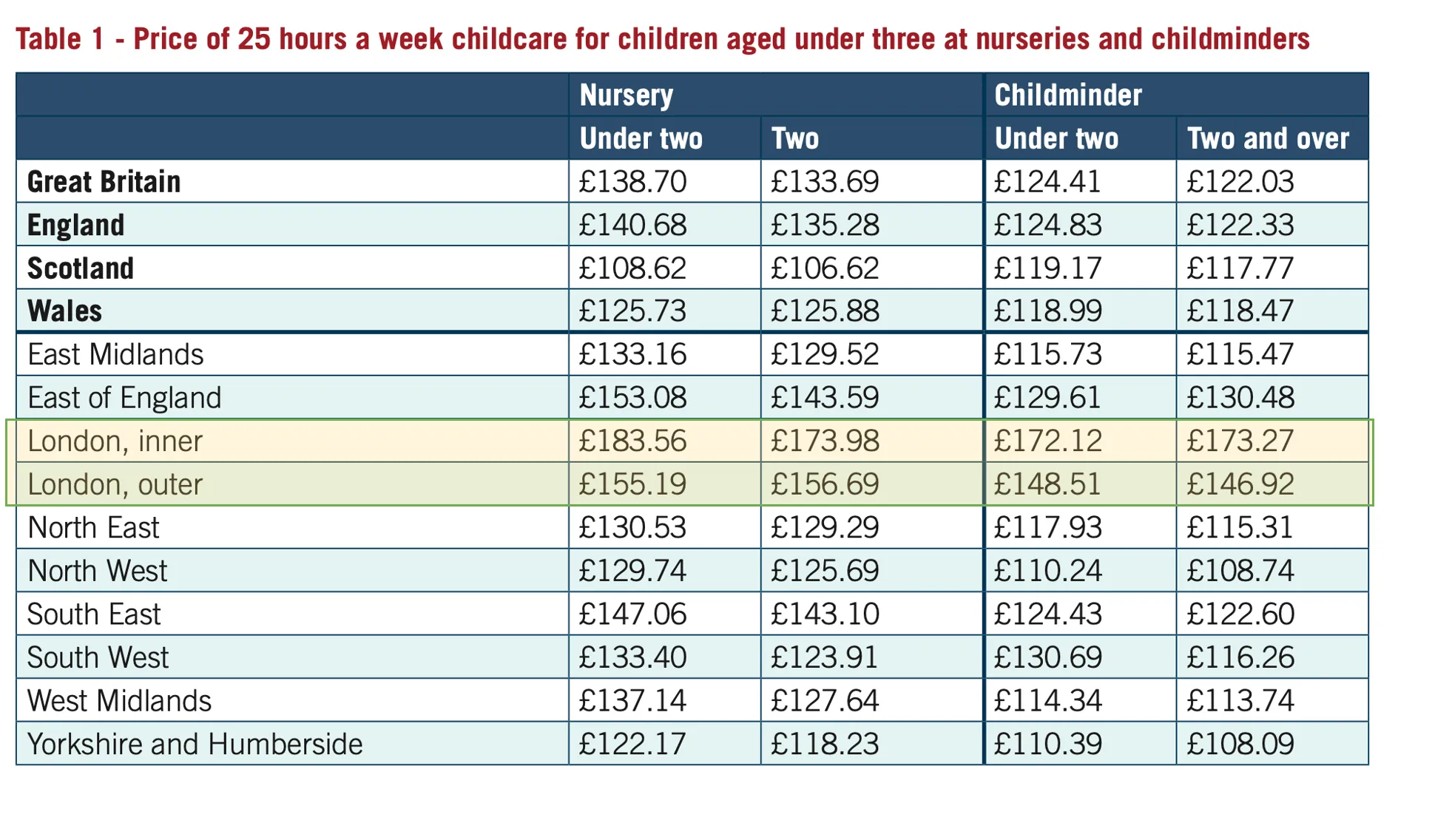

And according to Coram Family and Childcare’s Childcare Survey 2022, London has the highest childcare costs in the country, with 25 hours of nursery for under-2s in inner London costing £183, and in outer London £155.

A fairer city is possible

The data paints a challenging and difficult picture, and things aren’t going to get any easier. But poverty is not inevitable, and we know that a fairer city is possible. Across London there are hundreds of projects taking place every day to bring about the change we need – ranging from direct service delivery and community organising, to policy influencing and research. Many of these initiatives are led by the very people who are most affected.

In order to find the solutions that work and projects that will make real change, we need to understand the problems first. That means using facts and figures like these – but also listening to people’s lived experiences of the issues. Understanding how poverty works and how Londoners experience it is a vital step towards our vision of a more equal London.

********

It is precisely this point about listening – and responding to – people’s lived experiences which is underpinning the Policy Institute’s work on the cost of living crisis. We’re grateful to all our experts who gave their time so willingly and helped to shape the debate – and particularly to the participants who shared their thoughts. We will be publishing more on this in the coming months. In the meantime, if you have any questions then please do get in touch with the team at costofliving@kcl.ac.uk.

[1] The SMC measures whether households have resources to meet their immediate needs and take into account post tax earnings and income as well as benefits, tax credits and liquid assets. They then deduct inescapable recurring costs such as housing, childcare and additional costs faced by disabled people.