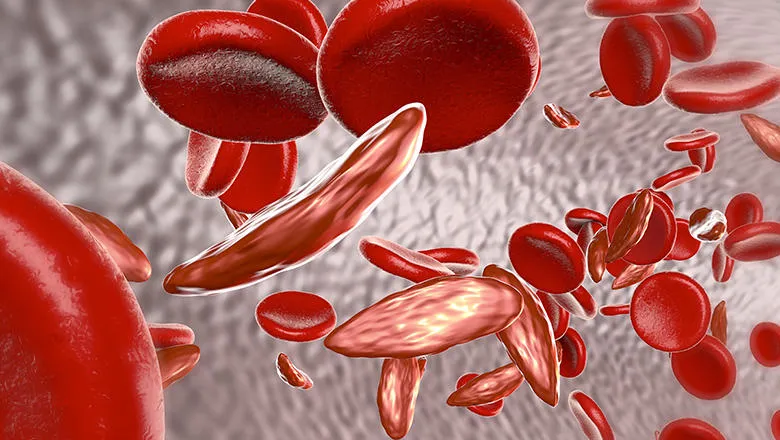

Sickle cell disease is the most common severe inherited disorder in the world, with estimates suggesting 7 – 8 million adults and children currently live with the condition."

David Rees, Professor of Paediatric Haematology in the School of Cancer & Pharmaceutical Medicine, and one of the Commission’s Lead Editors

13 July 2023

Experts urge governments to take action and provide basic levels of care for people with Sickle Cell Disease

A Lancet Haematology Commission has urged governments to take immediate action to provide basic levels of care for people with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), as the global impact of the disease is revealed to be much worse than expected.

A recent Lancet Haematology Commission claimed that reducing the burden of SCD requires substantial financial and political commitment to improving data-collection, diagnosis, treatment and training, but doing so will positively impact the lives of millions of patients and families worldwide.

The Commission published its report shortly after another recent study in The Lancet Haematology journal found that SCD’s contribution to the full global mortality burden – the combined number of deaths and years lived with a disability - was much greater than recorded. When SCD was considered one of multiple factors in global all-cause mortality, its prevalence was found to be almost 11 times higher than when counted as a single cause of mortality.

“Outcomes from sickle cell disease vary markedly with geography - the mortality rates of children with sickle cell disease in high-income countries is probably less than 1%, whereas it is more than 80% in some parts of Africa. The Commission identifies actions which must be taken to reduce the global burden of sickle cell disease over the coming decades, focusing on five main areas: epidemiology, neonatal screening, provision of standard treatments, development of new stem cell-based treatments, and training and education.”

With over half a million babies born with SCD in 2021, the Commission highlights how newborn screening for SCD can lead to babies with the disease receiving life-changing treatment before symptoms develop and calls for all babies worldwide to be tested for SCD by 2025 to prevent long-term complications of the disease.

The Commission also shines a light on the unequitable treatment of SCD, describing how access to important treatments like penicillin and blood transfusions are not easily accessible in low- and middle-income countries where most people with SCD live. There is a shortage of healthcare and scientific professionals with expertise in SCD, as well as a lack of trials aimed at developing novel treatments. This problem is particularly severe in most of sub-Saharan Africa and India.

The Commission says that in the context of increasing global inequalities, partly driven by racism, previous calls for action on SCD have been largely ineffective. There is an urgent need for all people with SCD to be given access to minimum specific health care no matter where they live and for funding programmes for research in all aspects of SCD to be prioritised and increased.