Controlling the spread of the coronavirus pandemic is as much about human behaviour as it is about the medical facts or government rules, so it’s no surprise that governments have turned to behavioural scientists for insights. Across two papers and six studies, our new findings cast doubt on the actual impacts of some of the most commonly used tools in the context of this crisis.

Dr Michael Sanders, Reader in Public Policy at the Policy Institute, King’s College London

12 August 2020

Doubt cast on use of some 'nudges' during Covid-19 crisis

Established interventions did not have the expected effects

The effectiveness of using certain behavioural science “nudges” to change attitudes or behaviour in relation to Covid-19 has been called into question by two new studies.

In a series of experiments, researchers from King’s College London tested nudges that have previously been shown to encourage people to think or act in desired ways.

They found that when used in the context of the coronavirus crisis, they did not have the expected effects.

Study 1: loss aversion

In the first study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Economic Letters, the researchers tested so-called “loss aversion” messages.

One of the most robust findings in social psychology is that people value losses more than they do gains of equivalent size.

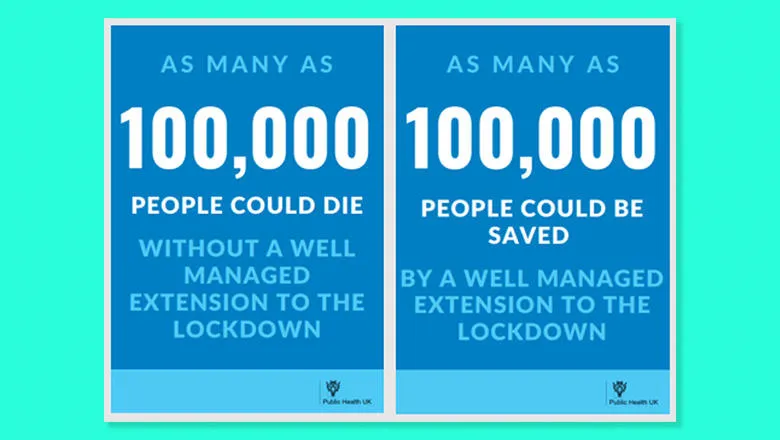

A message highlighting the potential lives lost without a well-managed extension to the lockdown was therefore expected to make respondents more cautious about Covid-19 than a message highlighting potential lives saved by a well-managed extension.

500 people were randomly assigned to be shown one of the two messages, which were presented as government information posters.

Respondents were then asked how long they felt the lockdown should last for schools, offices and different types of businesses, and about their intention to comply with public health guidelines, such as washing their hands more frequently and for longer and maintaining social distancing.

Differing from the established literature on loss aversion, the researchers found that highlighting potential lives lost did not make people more cautious about ending lockdown or more likely to say they would follow the guidelines.

The researchers suggest this may be because participants were already familiar with the anticipated death toll for Covid-19 with and without lockdown measures, or because so many people had already died in the UK at the time of the experiment (19 May 2020) that participants were effectively choosing between two very large losses, rather than a loss or a gain.

Study 2: behaviour change

In the second study, published as a working paper and currently under peer review, the researchers carried out a series of experiments testing a different set of nudges in April, May and June.

They found that the nudges increased respondents’ intention to comply with guidelines to tackle Covid-19 but did not have the expected result of actually changing their behaviour.

In the study, participants were randomly assigned to read one of three mocked-up online news articles about coronavirus.

The articles were identical except for their titles and opening paragraphs, with two containing messages informed by behavioural science research, and one containing a control message.

The first nudge message focused on high levels of compliance with the lockdown among the UK public, because highlighting positive behaviour as a widespread norm has been found to encourage others to engage in it.

The second nudge message focused on an older person particularly at risk of Covid-19 and unable to leave their home at all, as previous research has found that people are more willing to make sacrifices when there is an identifiable beneficiary.

The third message, which was presented to the control group, contained general guidance on how to maintain mental and physical wellbeing during lockdown.

Participants were then randomised to receive an extra nudge, in which they were asked to reflect on someone they knew who was more likely to be impacted by Covid-19 and then provide a written explanation of the steps they were taking to stop the spread of the virus.

Finally, participants were asked to rate their intention of leaving their home in the next five days, as well as their intention to follow public health guidelines.

The study found that, directly after reading the messages, participants who received the nudges were significantly more likely to say they would comply with the lockdown and follow the guidelines.

But when participants were asked again in follow-up experiments one and two weeks later, there was no difference in intention to comply among those who had been nudged and the control group.

And when asked to recall their behaviour in the intervening weeks, the groups who had received nudges were no more likely than the control group to report following the rules.

“We can only conclude that nudges activate good intentions, but people find it hard to follow through because of all the other influences on their behaviour that crowd out nudges on this occasion,” the study says.

Read the full studies

Sanders, M., Stockdale, E., Hume, S. and John, P. (2020) “Loss aversion fails to replicate in the coronavirus pandemic: Evidence from an online experiment”, Economic Letters.

“Nudge in the Time of Coronavirus: the persistence of behavioural messages during crisis”.