04 March 2020

Digital heart model will help predict future heart health, new study finds

Increasing computer power and novel algorithms could predict future heart health of patients

In recent times, researchers have increasingly found that the power of computers and artificial intelligence is enabling more accurate diagnosis of a patient’s current heart health and can provide an accurate projection of future heart health, potential treatments and disease prevention.

Now in a paper published today in European Heart Journal, researchers from King’s College London, leading the Personalised In-Silico Cardiology consortium, show how linking computer and statistical models can improve clinical decisions relating to the heart.

Lead researcher Dr Pablo Lamata, from King’s College London, said: “We found that making appropriate clinical decisions is not only about data, but how to combine data with the knowledge that we have built up through years of research.”

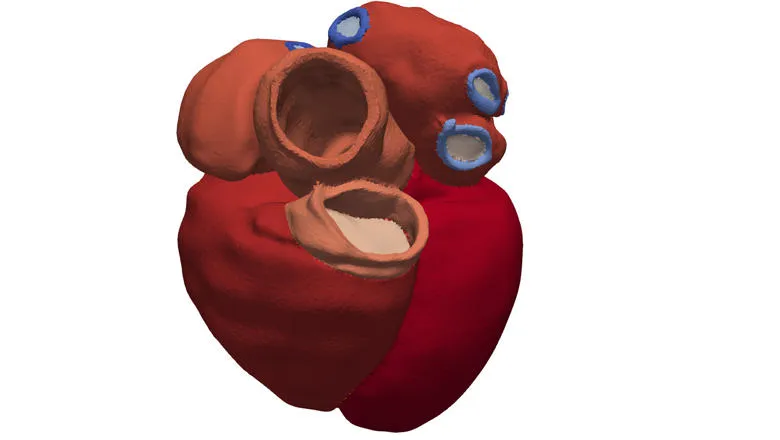

The team have coined the phrase the Digital Twin to describe this integration of the two models, a computerised version of our heart which represents human physiology and individual data.

“The Digital Twin will shift treatment selection from being based on the state of the patient today to optimising the state of the patient tomorrow,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

This could mean that a trip to the doctor’s office could be a more digital experience.

“The idea is that the electronic health record will be growing into a more detailed description of what we could call a digital avatar, a digital representation of how the heart is working,” said Dr Lamata.

Mechanistic models see researchers applying the laws of physics and maths to simulate how the heart will behave. Statistical models require researchers to look at past data to see how the heart will behave in similar conditions and infer how it will do it over time.

Models can pinpoint the most valuable piece of diagnostic data and can also reliably infer biomarkers that cannot be directly measured or that require invasive procedures.

Dr Lamata said more information about how the heart is behaving could be retrieved by using these models.

“We already extract numbers from the medical images and signals, but we can also combine them through a model to infer something that we don’t see in the data, like the stiffness of the heart. We obviously cannot touch a beating heart to know the stiffness, but we can give these models with the rules and laws of the material properties to infer that importance piece of diagnostic and prognostic information. The stiffness of the heart becomes another key biomarker that will tell us how the health of the heart is coping with disease.”

The team of researchers believe that the power of computational models in cardiovascular medicine could also provide us with more control over our daily heart health.

Much like the popularity of wearable monitoring devices, a digital twin of our hearts could inform about its current health and alert wearers to any risk factors.

“It is also the vision of people being more empowered and being more in control and aware of the impact of their lifestyle choices in the health of their hearts. We will have more wearables that can monitor aspects of our health rhythm, heart sounds or level of physical activity. This unit is also talking to the digital twin that lives in the hospital,” said Dr Lamata.

“It’s like the weather: understanding better how it works, helps us to predict it. And with the heart, models will also help us to predict how better or worse it will get if we interfere with it.”

The team of researchers say we could see the technology in action within the next 5-10 years.