25 July 2018

Artificial intelligence is demonstrating gender bias – and it’s our fault

Dr Muneera Bano, Lecturer in Software Engineering, Swinburne University of Technology

The data being used to train AI programmes is often gender-biased

Applications based on artificial intelligence are increasingly informing decisions in critical areas of our society – including strategy, defence and policymaking, to name but a few. This is hugely significant. The advent of AI promises to overcome human limitations of speed, processing and thought, opening up a whole new range of possibilities for how we live and work.

That, at least, is the optimistic view. A more pessimistic take suggests that AI, rather than doing away with our cognitive constraints, may actually entrench them further in certain respects – something that may have implications for gender equality.

While AI programmes themselves are not biased, we humans can inadvertently train them to be. Such programmes are like newborn babies, voraciously absorbing all the information that is fed to them and learning from it. But if the data they are given is biased, the AI will exacerbate this bias with its vastly superior computational powers.

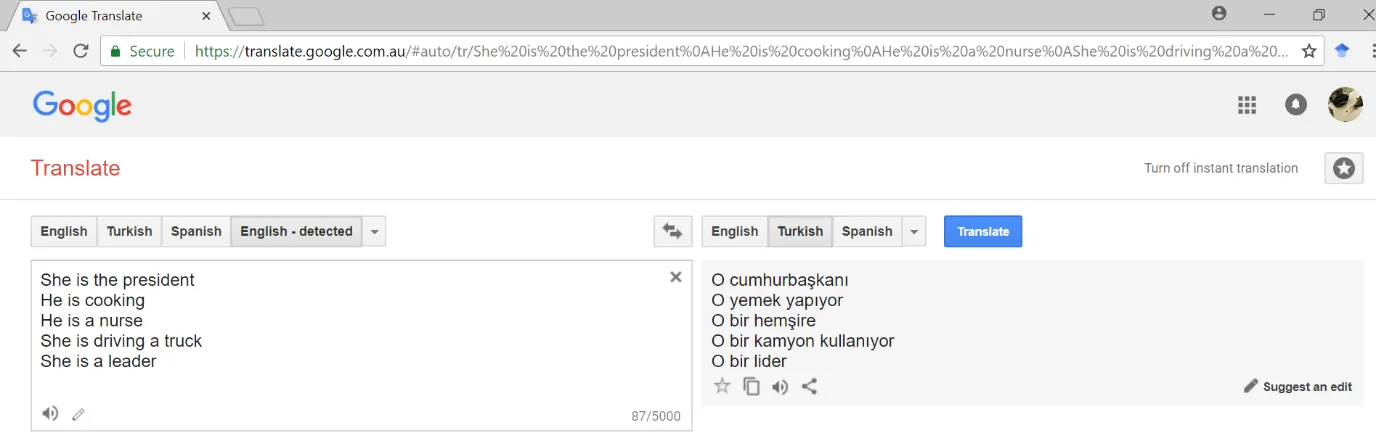

We can catch a glimpse of this threat through a small experiment using Google Translate. Below are some gender-associated phrases in English:

- She is the president

- He is cooking

- He is a nurse

- She is driving a truck

- She is a leader

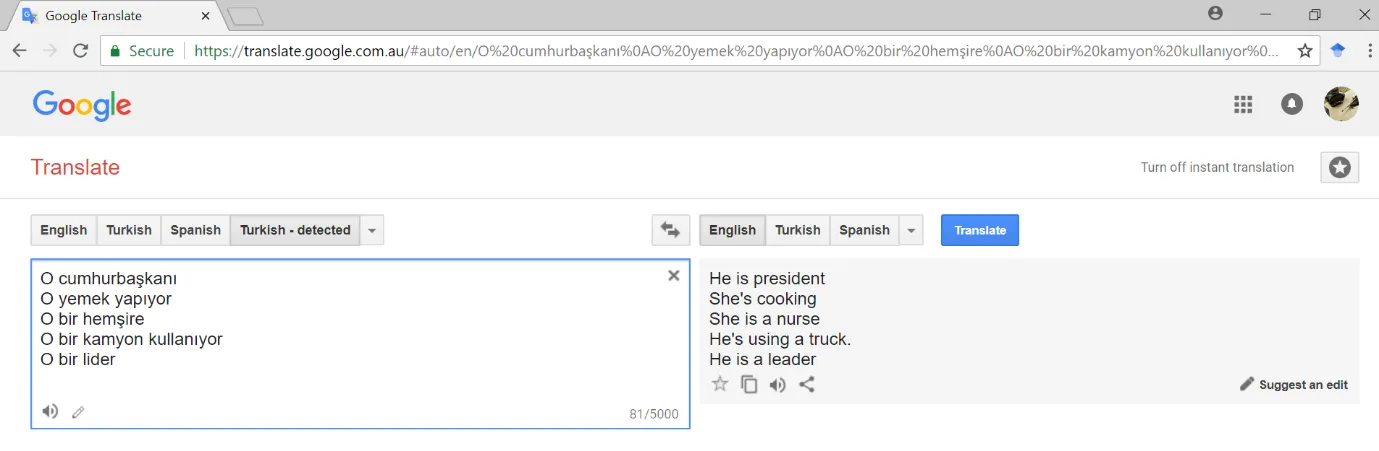

If you translate these into Turkish, and then back to English, you get the following results:

- He is president

- She's cooking

- She is a nurse

- He's using a truck

- He is a leader

What happened?

Turkish is a gender-neutral language, and in translation from English to Turkish, the gendered pronouns were lost. Translating back to English required the AI-based translation algorithm to analyse and associate a gender with the type of role being described. The data that is used to teach the AI has strong gender stereotypes. The AI therefore decided it must be HE who is president, driving a truck or a leader, and it must be a SHE who is cooking and is a nurse.

The question is, where is this gender-biased data coming from?

AI algorithms are software that is written to learn and create associations in large amounts of existing data. The algorithms’ decisions are as good as the data they utilise for training and understanding. If an algorithm is given a larger amount of text or pictures depicting women doing chores at home and men doing work outside the home, it will increase the statistical probability of these associations and will learn to use them for its future decision-making processing.

The field of computing has always been male-dominated, and the learning data sets for AI are created by the majority of male computer scientists who lack a feminist point of view. The data sets have been proven to have both conscious and unconscious gender biases, and to be biased in how they are collected – namely, by acquiring what is cheap and easily available.

Social media provides a conveniently available and cheap source of data for training AI, especially in social science research. Twitter and Facebook have been used extensively in monitoring the social trends and sentiments of people around the globe. Twitter has around 330 million monthly active users, with 500 million tweets being sent per day. The accessibility and volume of that data has led to a lot of research using tweets as training data sets for AI algorithms to learn social trends.

The repercussions of gender-biased AI

Online hate speech has escalated the war on gender equality in cyber space. The amount of hateful content posted on social media against female public figures is far worse than that targeted at their male counterparts. This content provides a pattern of gender-based hate and stereotypes for AI to learn from.

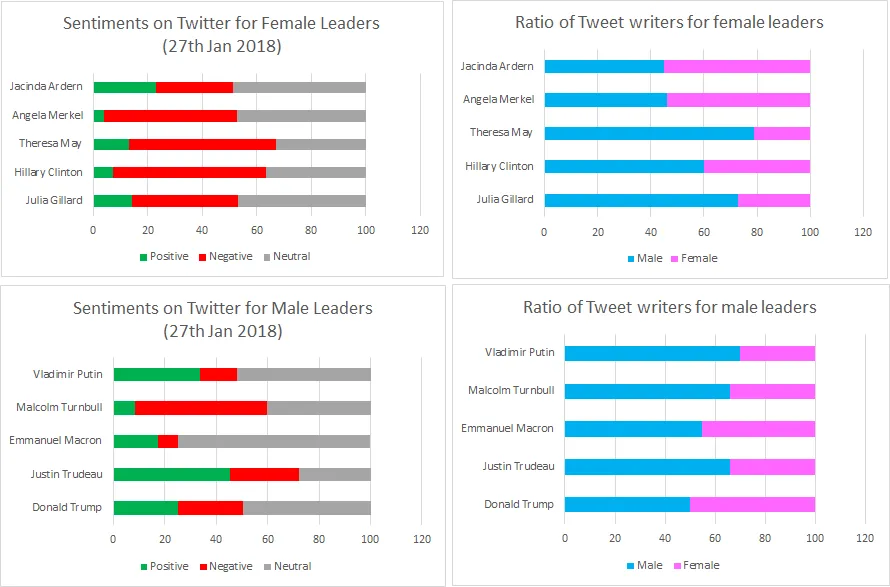

We carried out research which tracked tweets associated with the names of five male and five female leaders on 27 January 2018. We found that, overall, more negative sentiments were expressed on that day against the female leaders compared to the male leaders. Male Twitter users, on average, also tweeted about the leaders more than female users.

A similar experience can be had on Google Image Search. If you enter the words ‘President’ or ‘Prime minister’, almost 95% of the pictures that appear in the results are of men. From this type of data and the social media data described above, AI can learn two obvious facts: first, that there aren’t many women in leadership positions, and second, that female leaders are less likeable in comparison to male leaders.

These online posts and tweets are not ephemeral things that eventually vanish into the ether; they are recorded and eventually contribute to the corpus of data about online social trends. This data will be used in making future decisions and creating a social reality through increased dependence on AI. The recent Cambridge Analytica scandal has demonstrated how Facebook was used to impact the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election by manipulating user data.

In the past, history was written by the victors. Now, it is being written in cyber space, by those who create online content. Online gender bias is a threat to equality, and if not addressed now, will make life much harder for women in the future. The World Economic Forum has estimated that it will be another century before we achieve gender equality, but if we do not address the biases of AI now, even this may be too optimistic.