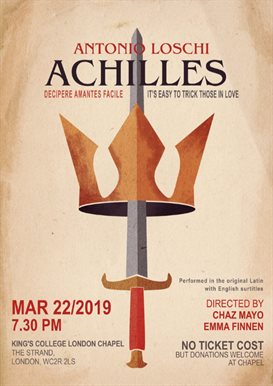

2019 Achilles

2019 Achilles

By Antonio Loschi

Hector is dead, Achilles is triumphant, Troy will soon fall, abandoned by the gods. In the city, only the weak remain: ancient Priam, grief-crazed Hecuba, the coward Paris, the maiden Polyxena. But Achilles is in love with Polyxena, and that may be enough to destroy him…

Written c. 1387-90, Loschi’s Achilles is the first mythological play of the Italian Renaissance. Following Senecan models, but with a bitterness all his own, Loschi transforms the world of epic heroes into tragic farce.

Read the full programme for the 2019 Latin Play.

2018 Ignoramus

2018 Ignoramus

By George Ruggle

George Ruggle’s (1575-1622) Ignoramus was a major hit. First performed in 1615 at Cambridge for the entertainment of the visiting King James I, it was performed repeatedly well into the 18th century, reprinted multiple times (11 editions between 1630 and 1787) and also translated into English at least three times in the latter part of the 17th century.

Ruggle’s sprawling work – apparently running in its original performance to over five hours – satirises the character and (especially) the poor Latin of ‘Ignoramus’, a common lawyer in a town of scholars (Bordeaux). As such, it belongs broadly to the enduringly popular genre of legal satire – a kind of Better Call Saul for the early 17th century. (More closely contemporary examples include Donne’s Satires of the 1590s and the Trebatius scenes in Jonson’s Poetaster, 1601). The specifically dramatic tradition to which it belongs is that of Plautus’ Pseudolus (itself a popular school play), though Ignoramus is based most directly upon an Italian version of Plautus’ play (Giambattista Della Porta’s La Trappolaria, c. 1590).

The most distinctive feature of the play is its linguistic inventiveness: Ignoramus’ hodge-podge of half-baked Latin,

English and French is still very funny".

Dr Victoria Moul (Classics, KCL)

Read the full programme for the 2018 Latin Play.

2017 Jephthes

2017 Jephthes

By George Buchanan

Published in 1554, George Buchanan's Jephthes re-tells, in the metres of Seneca and the spirit of Euripides, the Old Testament story of Jephthah, whose rash vow before battle led him to sacrifice his daughter to the Lord.

The story of Jephthah is only briefly sketched out in the Old Testament book of Judges (11.30-39). A great warrior but an exile, Jephthah is summoned to help the Israelites defeat the Ammonites. In his eagerness to secure a victory, he makes a vow to God that, should he prevail, he will sacrifice the first thing he sees when he returns home. God grants him victory but, upon his return, it is his only daughter who comes to meet him. He does not break his vow.

Buchanan’s open exploration of a crucial question, along with his acute sense of the

tragic in this play, is what made it popular with a range of religious reformers, and what

makes it so worthy of re-performance to this day."

Dr Lucy Jackson (Classics, KCL)

See a full programme for the 2017 Latin Play.

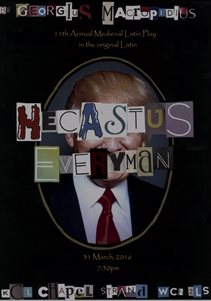

2016 Hecastus

2016 Hecastus

By Georgius Macropedius

Everyman, I’ll go with thee, and be thy guide; in thy most need to go, by thy side.

This motto, familiar from the first page of all Everyman editions of literary classics, borrows a line from the English medieval morality play The Summoning of Everyman (dating in its surviving form from the fifteenth century, though performed, in a modern version by Carol Ann Duffy, as recently as 2015). Hecastus, an allegorical Latin drama written in 1539 by the Dutch humanist, playwright and schoolmaster Joris van Lanckvelt (1487-1558, known as ‘Georgius Macropedius’ in Latin) is a version of the same story.

Hecastos is Greek for each man and his tale is part of a long and still living tradition to which John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Rudyard Kipling’s poem 'Tomlinson', and the film 'It’s a Wonderful Life' all loosely belong. The basic plot is that of a successful but complacent man of the world who, confronted suddenly by imminent death, finds that none of what he has valued in life – riches, power, friends and patrons, even his partner and children – offers him any hope of reprieve, or even loyal companionship in his final hours. Instead, he must turn to long-neglected Virtue and (in Macropedius’ version) her younger sister, Faith – the only ‘characters’ in the play who agree to accompany him to his judgment and who, in the final scene, save his soul from damnation.

The combination of the tragic plot with an emotional register typical of comedy is a vivid demonstration of the religious message of the play."

Dr Victoria Moul (Classics, KCL)

See a full programme for the 2016 Latin Play.

2015 Geta

2015 Geta

By Vitalis of Blois

'Geta', a twelfth-century elegiac comedy, re-tells the story of Amphitryon, one of the numerous comedies by the profilic Roman playwright Plautus (c. 254–184 BC).

The main plot involves the double deception by the philandering Jupiter, assisted by his son Archas (Mercury), who impersonate the absent Amphitryon, and his factotum, the eponymous Geta, to gain access to Amphitryon’s beautiful, unsuspecting wife, Alcmena, while Amphitryon is away, studying philosophy in Athens. The return of the real Amphitryon provides opportunity for a hilarious encounter between the vainglorious Geta, now swollen with delusions of superior logical skills picked up in Athens, and the pseudo-Geta, who convinces him that he (the real Geta) is not Geta, and thus, logically, Nothing.

This is comedia—hilarious, ingenious, learned—ridiculing pretentious false logic as it explores the

humorous possibilities of duplicity, gullibility, impersonation, and illicit love."

Anne J. Duggan (History, KCL)

See a full programme for the 2015 Latin Play.

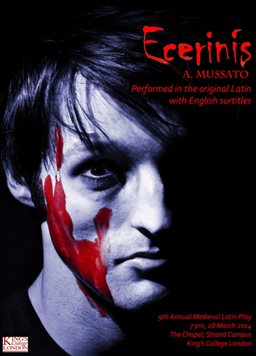

2014 Ecerinis

2014 Ecerinis

By Albertino Mussato

Written in 1315 in Padua, Ecerenis tells the story of the bloody career and bloodier end of Ezzelino da Romano, a tyrant who had terrorised northern Italy half a century earlier.

Ecerinis brought together Mussato’s admiration for Seneca, his talent as an historian and his political passions. The model of Ecerinis (five acts, a complex metrical structure, a prominent role for the chorus) is Seneca’s tragedies and particularly Thyestes; the subject is the story of the unforgotten tyrant of the March of Treviso, Ezzelino III da Romano (1194-1259); the political message is a warning against the plans of Cangrande della Scala (1291-1329), lord of Verona, who was in those years the most serious threat to Padua’s libertas. The tragedy was recited in the public palace of Padua before a crowd of citizens; it was meant to entertain and instruct them, emphasising the Roman legacy of the city of Livy. Mussato offered antiquity as a repository of moral and political values, not just aesthetic models. Like many of his beloved republican Roman writers, he, too, paid a high price for his involvement in politics and ended his life in melancholy exile in a small town of the Venetian lagoon.

The story is one of darkness and retribution, showing the suffering that one tyrant can wreak upon his land - a message that is relevant, one could argue, in today’s world."

Doug R. Dunn and Serena Tabacchi (Directors)

See a full programme for the 2014 Latin Play.

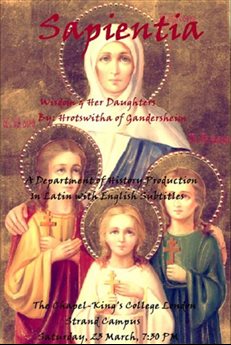

2013 Sapientia

2013 Sapientia

By Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim

Presented in nine Scenes, Sapientia is the story of the triumph, through endurance and extraordinary martyrdom, of the three sisters Fides, Spes, Karitas (Faith, Hope, Charity), daughters of Sapientia (Holy Wisdom), against the attempt by the Roman emperor Hadrian (AD 117–38) to force them to renounce their Christian faith. They represent the female martyrs, like Felicity and Perpetua, Agatha, Lucy, Agnes, Susanna, Cecilia, and Anastasia, whose legends were well known.

See a full programme for the 2013 Latin Play.

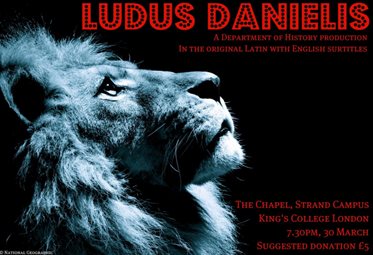

2012 Ludus Danielis

2012 Ludus Danielis

Described (Bevington, Medieval Drama, 137) as ‘a work of brilliant pageantry’, this masterpiece of religious drama links the Christmas celebration of the birth of Christ in twelfth-century Beauvais (c. 1140) with the dramatic events in Babylon more than 1600 years before (c. 538 BC). The historical background is the second captivity of the Jewish people, which followed Nebuchadnezzar II’s destruction of Jerusalem, despoliation of the Temple and mass deportation of the Jews to Babylon (587/6 BC), whence they were freed (539/8 BC) by Darius the Mede (Cyrus II of Persia, 559–30 BC). The scholars and young clerics of the cathedral school appear both as themselves, acclaiming the coming of Christ, and as members of the Babylonian court under Belshazzar and Darius. Exploiting to the full the dramatic possibilities of processions accompanied by chants (conductus, prosa) and music adapted from liturgical practice, the grand drama unfolds around two sensational events in the Book of Daniel (Dan. 5–6).

Bringing an old story in an old language to life in a way that will be interesting and

relevant to modern audiences has been a wonderful challenge, and we hope that

through this you will be able to have a sense of the timeless energy in these plays."

Directors' Notes

See a full programme for the 2012 Latin Play.

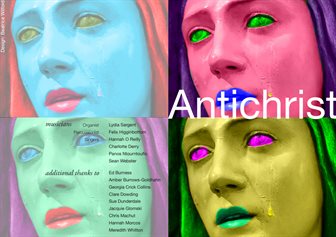

2011 Ludus de Antichristo

2011 Ludus de Antichristo

In simple and elegant rhyming couplets, the Ludus de Antichristo narrates the coming to earth of the Antichrist, as predicted in the Old and New Testaments. Antichrist is welcomed as the Messiah by the Church and Synagogue, and by the Holy Roman Emperor and the kings of Europe and Asia. His ultimate aim is to submit the whole world to Satan’s power, before he is unmasked by the true prophets of God.

The text survives in only one manuscript, from the Bavarian abbey of Tegernsee. The author is unknown, but he must have been writing in the second half of the 12th century, before the death of Emperor Frederick I in 1190. The play offers nothing less than an enactment of the end of history, as pictured in the medieval religious imagination. This vision is built on a dramatic paradox: history reaches its accomplishment in the submission of all the earth to Satan’s emissary, and yet the final victory does not belong to the Evil One. The pride of newly formed nations, the messianic expectations of the emperor and his crusaders, the deluded patience of the Jews, the wickedness of a corrupt Church – all make for a world that is easy prey to Antichrist, and all will succumb to his violence or deceipt. But the faithfulness of God must prove greater than the unfaithfulness of men.

Despite a few nervous moments along the way, my overwhelming memories are of how fun rehearsals were and I’m already missing working with everyone. Working with directors from RADA and professional musicians, and performing in such magnificent surroundings was a unique experience. We were all really proud of the final result, and it was definitely worth the hard work put in by everyone."

Abby Stevenson (MA Medieval History) who starred as the Antichrist

See a full programme for the 2011 Latin Play.

Read the script and translation of this play by Daniel Hadas.

2010 Ludus de Nativitate

The Ludus de nativitate, uniquely preserved in a manuscript from the Benedictine monastery of Benediktbeuem in Bavaria (home of the Carmina Burana), is a product of the twelfth-century renaissance in Latin letters, science and theology. Although the core of the play (ludus) is the familiar story of Christmas as told by St Matthew, it is more than that. In its Prologue (Scene 1), the short drama ingeniously presents the tension between Christian and Jewish interpretations of the Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah. Where Christian theologians saw Isaiah's famous prophecy as a foretelling of the birth of Christ, Jewish authorities saw it as a promise of a Messiah, but one which was yet to bet fulfilled.

The play thus opens with a disputation between Isaiah, Daniel, the Sibyl, the synagogue leader, and 'the Prophets', which concludes, in words of attributed to Augustine, that the Jews should learn the meaning of their own scriptures and acknowledge the birth of the new king. Equally interesting is the discussion between the kings in Scene V, which reflects the revival in astronomical and astrological studies in the twelfth-century schools, under the influence of the 'new' scientific learning translated from Arabic in the works of scholars like the English Adelard of Bath. Noteworthy is the knowledge of the planets, and the confident assertation that the 'star' that announced Christ's birth was neither star nor planet, but a comet (sit cometa) - one of the possibilities discussed by modern astronomers. The play was devised for performance (in chant) by young monks on the feast of the Epiphany, which celebrated the revelation of Christ.

See a full programme for the 2010 Latin Play.

2009- 2006 Latin Play

By Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim

Directed by Kellyn Johnson

Filius Getronis is one of four anonymous St Nicholas plays from a group of ten dramas found in a c.1200 manuscript known as the Fleury Playbook. St Nicholas was one of the most popular saints of the period; his cult spread rapidly in Europe following the 1087 translation of his remains from Myra (Turkey) to Bari (Italy). He became famous for protecting children, sailors, scholars and the oppressed, and may have been associated with the Crusade movement. His cult gave birth to a number of plays, based on legend rather than on the Bible or liturgy. Filius Getronis tells the story of a boy, Adeodatus, who is restored to his parents by St Nicholas after spending a year in captivity at the court of King Marmorinus.

See a full programme for the 2009 Latin Play

By Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim

Directed by Mara Lockowandt

The 2008 Latin Play tells of the desire of the Roman commander Gallicanus for Constantia, the daughter of the emperor Constantine, and the commander's subsequent conversion to Christianity. The drama begins on the eve of Gallicanus' departure on campaign against the Scythians, when he asks the emperor for the hand of his daughter in marriage. Constantia, however, happens to be the a consecrated virgin...

See a full programme for the 2008 Latin Play

By Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim

Hrotsvitah was a tenth-century nun in Ottonian Germany, at the powerful imperial convent of Gandersheim. The convent had close connections with the imperial court through the male relations of the canonesses and nuns, linking it to the Ottonian renaissance.

Hrotsvitha's plays make her important as not only the first Christian playwright but also as a female author. Her plays are a response to Terence's works, which were well known, and possibly performed, at the Ottonian court. Debate over the performance of her work has shifted in line with the conceptions of women's capability, much in the way that is has now been accepted that a woman could have written Heloise's letters. Hrotsvitha wrote a cycle of complementary plays and poems. Dulcitius is remarkable for its farcical elements

See a full programme for 2007 Latin Play

By Vitalis of Blois

Directed by Liisa Smith

Aulularia was the second comedy composed by Vitalis, about whom little is known other than that he lived and wrote in the first half of the 12th century. He was probably a cleric, and his two plays Geta and Aulularia were most likely written during the period 1125-1145. From the mid-12th century his works were read in the schools and cited in the writings of other authors.

Vitalis is superior to many other poets of his age in that he wrote in a correct and elegant Latin, which, in Aulularia, especially, has the capability of transforming rhetorical artifice, through the use of irony, into humour.

Aulularia follows a classical plot, while at the same time satirising the medieval philosophical schools. Much of the wit derives from the elevated language of the philosophical schools being put in the mouths of fools and slaves who bungle the complex terminology, a situation that would have appealed to a medieval audience.

See a full programme for the 2006 Latin Play