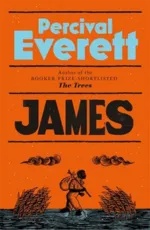

James by Percival Everett, reviewed by Jack Casson

Everett takes a welcome break from his typical post-modernist style to narrate a thought-provoking and, quite frankly, heart-wrenching tale of camaraderie, trauma and perseverance. Lifted from the literary spiritualism of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Everett combines fiction with reality in his own interpretation of the slave narrative that will leave readers in a ball of tears. Re-told through the perspective of the enslaved Jim from Twain's original tale, Everett questions the elusiveness of freedom and what it means to take away the voice of the oppressed, all whilst constructing a vibrant social and geographical landscape of Mississippi that only furthers Jim’s complex position as both hunted and hunting for freedom. James is undoubtably a worthy contender for the Booker prize in its rich yet accessible complexity… just make sure to have a box of tissues as you read.

James by Percival Everett, reviewed by Nathan Lewis

In his latest novel James, Percival Everett gives a new name and a new voice to a character from one of the most famous works of American literature. In Everett’s poignant reimagining of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Jim – James – is not a secondary character at all: he narrates his own story with wit, intelligence, and humanity.

Using language – particularly the concept of ‘code-switching’ – to interrogate the caricatured portrayals of enslaved people in Huckleberry Finn, Everett adds new depth to James’ character. Though the novel provides a crucial opportunity to reexamine historical narratives about race in America, Everett’s James also stands as a powerful story in its own right. It undoubtedly has its dark moments, which can make it a challenging read. However, the subject matter is sadly necessary to confront, and Everett’s tale blends humour, philosophy, and friendship into the moral complexity and exploration of identity, making James a worthwhile and important read.