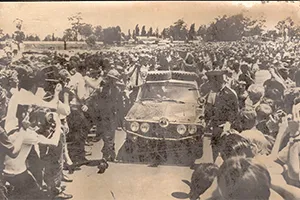

Tony’s Hunter became the first winner of the London-to-Sydney Marathon

Tony’s Hunter became the first winner of the London-to-Sydney Marathon

You came back to the UK in 1983.

I worked in the glass industry at Pilkingtons, then as a consultant to the GKN Group. The remit was simple: ‘We’ve been a major supplier to the British Motor Industry for 50 years. Give us a strategy for being the preferred supplier into the next century.’

My solution was to supply sub-assemblies to the car makers as they are required on the final assembly tracks rather than by function, for example, including brakes, etc. This is now general practice across the industry and it is still taught as part of the mechanical engineering degree at Cambridge.

You then moved into higher education…

I was appointed Visiting Professor at Loughborough with the remit of Design for Manufacture. I also became Design Fellow at Imperial College. I was responsible for a joint masters degree in Product Design with the Royal College of Arts.

You also worked on early electric vehicles…

Around 1967, I was contacted by the Mayor of New York. He said the yellow cabs were choking the city, so could we make them electric. Even before the internet, it took me about half an hour to find out that the major polluter of New York was the power station across the river. If the cabs went electric, the extra pollution from the power station to charge them would makes things even worse. Idea abandoned!

In my own company, I developed what I called the GVT, Global Village Transport. This was a basic range of vehicles for urban and rural use around the world. It started with a small diesel engine and transmission I’d designed, but I was persuaded to go electric. This was too soon in the development of that technology. I should have started with the diesel engine, then gone to electric later. Hindsight is always perfect!